Seabirds in the Coal Mine

by Amanda Flynn

Emily Burton grew up in the Scottish Midlands — the farthest away from the North Sea you can get in the United Kingdom. She always had an interest in the outdoor world, but it wasn’t until she began working in dolphin and whale conservation that she discovered the beauty of the undersea world and seabirds – whose part in that rich ecosystem is now in trouble.

“I think that the water is quite overlooked. It’s difficult for people to understand how incredible it is and how important it is for us, because it feels a long way away, right? It is not quite as easy as connecting people with the wildlife on land,” said Burton.

While working at several conservation charities, the 26-year-old found her admiration for seabirds, becoming the volunteer coordinator at the Scottish Seabird Center in 2019. She has since become the conservation projects officer.

Located on the south shore of the Firth of Forth in the town of North Berwick, the Scottish Seabird Center is a conservation and educational charity that offers boat trips and learning opportunities for people to learn more about Scotland’s seabirds and the importance of protecting them.

While walking through the streets of this seaside town, the smell of salt fills the crisp coastal air and the sounds of seagulls can be heard at every turn.

One seabird species in particular seems to be the mascot of North Berwick — the puffin, a plump black and white species with a distinctive orange bill and webbed feet.

At the gift shop of the center, visitors can find cozy stuffed puffins, colorful puffin socks and painted puffin mugs. Just a short seven-minute walk from the center, there is a restaurant called The Puffin and a home with a sign that reads “Puffin Cottage.”

“I’ve always felt very connected to the outdoors,” said Burton. “I think as I grew a wee bit older, I started to think a wee bit more about things like climate change and the climate crisis.”

The importance of protecting Scotland’s seabirds has become a priority for conservationists recently after fatal events, known as seabird wrecks, occurred at the end of last year.

Last autumn and into the winter, throughout Scotland and other parts of the UK, weak and dead seabirds washed ashore, raising concern from the public — one incident in particular involved more than a hundred dead puffins washing up along the northeastern shores of the Orkney and Shetland islands.

Dr. Leah Hunter, a veterinary surgeon at Flett and Carmichael Veterinary Surgeons, cared for seven of these puffins last December.

Hunter said members of the Orkney community were finding cold and weak puffins in the sea, being washed ashore by the tide.

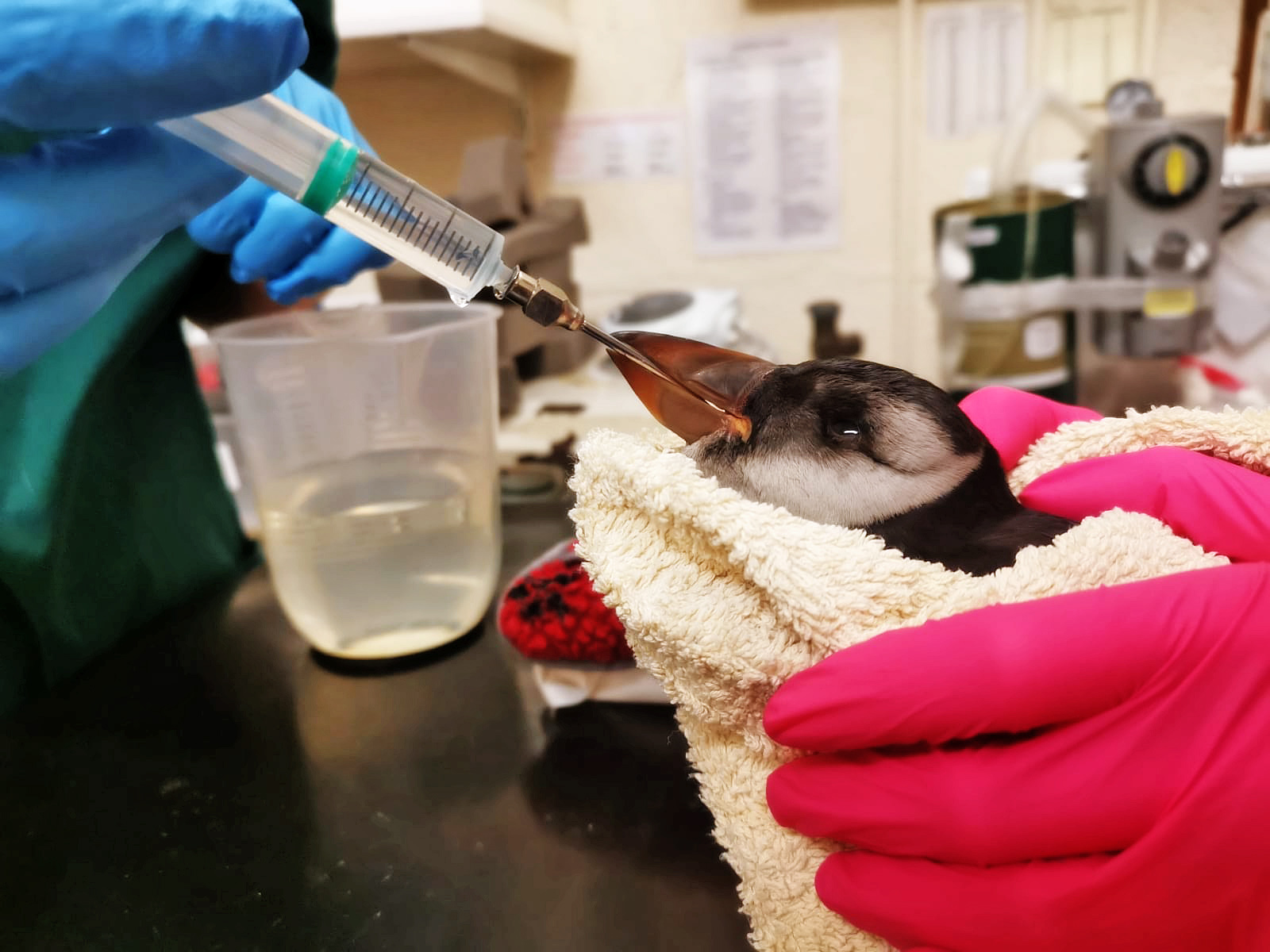

When brought to the practice, the puffins were kept warm in kennels with heat pads. Once they reached a stable body temperature, the puffins received an electrolyte mixture through a stomach tube for hydration and were fed a fish mixture.

Nonetheless, Hunter said most of the puffins died.

“As a nature lover, I felt concerned for the seabird populations in general seeing the sheer volume of dead birds washing up but I also felt sorry for the individual birds affected,” said Hunter.

It is not unusual for seabirds to wash ashore due to extreme weather, but this incident seemed out of the ordinary to scientists.

On an October day on the east coast of Scotland, Paul Walton was visiting a lagoon reserve owned by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB). Little did he know, he would make an unsettling discovery that day.

While looking at the shallow waters, Walton, who serves as the head of habitats and species at RSPB, was observing a seabird species known as the guillemot. Inside a lagoon, one bird looked “really, really sick.”

“It was diving repeatedly over and over and over again. The diving behavior and guillemots is something I personally studied,” said Walton. “It was really quite distressing because I knew that behavior was in the wrong place.”

Walton describes being “slightly obsessed” with seabirds since he was 6. Prior to being with the RSPB, he worked at Glasgow University as a seabird biologist.

The unusual behavior observed by Walton and others, raised concerns from scientists and conservationists regarding the future of the UK’s seabirds.

Last November, The British Trust for Ornithology, said that the UK puffin population could decline by as much as 90 percent in the next three decades, if the marine environment continues to change due to rising water temperatures.

According to Scotland’s Marine Atlas, Scotland plays an exceptional role in the breeding process, with its islands being the nesting hub for 24 species from April through August.

Walton said that the abundance of hard, volcanic rock makes Scotland a prime place for more than five million seabirds to colonize and breed.

When looking at the corpses, scientists are able to analyze the state of the sea and gain an understanding of what might be taking place underwater.

Scientists also have been investigating seabird’s food supply being at risk, which Walton describes as being “one of the big drivers of the [population] decline.”

A seabird, such as a puffin, should normally weigh around one to two pounds — Walton said the seabirds he and other scientists found weighed around half of that.

“The corpses we were finding were really light. They were very underweight. They were completely emaciated,” he said.

Dr. Francis Daunt of the UK Center of Ecology and Hydrology (UKCEH) said he has closely been watching these seabird wrecks – food supply being one of the focuses on the research.

“In terms of the food availability, the first question we’re working with fish biologists is to understand whether any of the food was lower than usual,” said Daunt. “We’re also working with remote sensing scientists to really understand whether there were any conditions that might have led to lower abundance of fish prey.”

Daunt, who has “always had an interest in birds,” has been working at the UKCEH for 20 years — he currently is studying causes of seabird population changes.

In-depth research is ongoing, but he said, “With an event like this, what you’re looking for is what’s called an anomaly. You need to look at fish distributions and abundance, and how you’re looking for something that’s different to what’s been seen in other years … You’re looking for something that tipped birds over the edge into a serious decline in condition and death.”

Burton recalls feeling “very sad” but also “curious” about these wrecks.

Similarly to Walton, Burton observed odd behavior along the coast.

“We were seeing things like razorbills, guillemots, very close to the coast around the harbor. At that time of the year, they should have been out in the open water,” said Burton.

Burton and the team at the center noticed the seabirds were, oddly, not showing any fear of humans.

“I think they were so obviously at that point, so desperate to try and find food. We knew that something was going on, something suspicious,” she said.

Burton defines seabirds as an “indicator species” for marine life, since “[seabirds] rely on a healthy, thriving, marine food web.”

In other words, seabirds are the canary in the coal mine.

“I think the climate change question is probably at the heart of everything we’re thinking about. It’s complicated,”

“I would say anything that impacts the marine food web will in some way, whether big or small, have an impact on seabirds. Everything going on under the water is connected,” said Burton. “When something starts to go wrong in one area, eventually it will feed up through to everything else.”

Walton said each year the North Sea mixes nutrient-rich water for phytoplankton to grow on the top layers of the water. In the spring, phytoplankton bloom for zooplankton to eat. Fish eat the zooplankton, seabirds eat the fish.

“It’s a very efficient food chain. It means we have this large population,” he said.

Walton said starvation stems from a domino effect.

“The zooplankton starve, there’s no food for the fish, there’s no food. So the food supply for these birds has gone down,” he said.

Food availability is not the only cause under investigation. The birds’ strange and unusual behavior raises the question of another cause – toxic poisoning from algal blooms.

Algal blooms are a rapid growth of microscopic algae in the water. They can produce harmful toxins that can lead to mortality in vertebrates, such as birds.

Though still being investigated and hard to detect in corpses, algal blooms may be a cause for the massive deaths, Walton said.

“A sudden bloom in the sea can actually be very toxic and can find a way into the food chain. It has been recorded in the past that seabirds have been behaving strangely, dying in an unusually large number,” said Walton. “We noticed at that time, last September, October, there was a huge, massive algal bloom in the central North Sea and we think that it could be related to that.”

Avian flu was another possibility for these wrecks, but Daunt said over 100 birds were tested and each came back negative.

So, what does this all mean?

“The marine environment is a very complex place where there’s a number of different things all happening at once. It’s quite unusual for there to be a single cause,” said Daunt.

However, this population decline and increase in wrecks has sparked awareness of the ever-present threat of global warming and its effect on marine life.

“I think the climate change question is probably at the heart of everything we’re thinking about. It’s complicated,” Daunt said.

Walton said there’s a possibility that algal blooms are being induced by warming temperatures.

“There is some science that is beginning to point to climate change being a factor that will increase the frequency of algal blooms in the North Sea,” said Walton. “Essentially, when these birds are washing up, I’m thinking one way or another, it’s very likely that climate change is implicated in this.”

Last November, Glasgow hosted COP26, which was a United Nations Climate Change Conference. – Walton and other members of RSPB, along with nature conservation organizations were in attendance, demanding action.

“We tried to draw attention to … these seabirds being washed right on the doorstep of COP26,” said Walton. “We had some sort of good traction with our messages because of that.”

“Humanity needs to really step up several gears, in terms of our response to climate change,” said Walton.

Walton said one solution is to invest largely in offshore wind power – something he said is a “profoundly ironic dilemma.”

“There’s a huge uptick in offshore wind developments. We know [wind power] must be part of our response to the climate emergency that we’re facing. But, we also know with deep and profound irony that wind turbines kill seabirds in quite big numbers,” Walton said.

Clearly there are no easy answers to solving this crisis, but Burton believes education is key to understanding and communicating the threats seabirds face.

In the meantime, Burton said that there is a rich diversity of marine life that needs protecting.

“We’ve got lots of very important islands, both for seabirds, and for other species on the coast of Scotland … I think the coasts around Scotland also hold massive potential.”