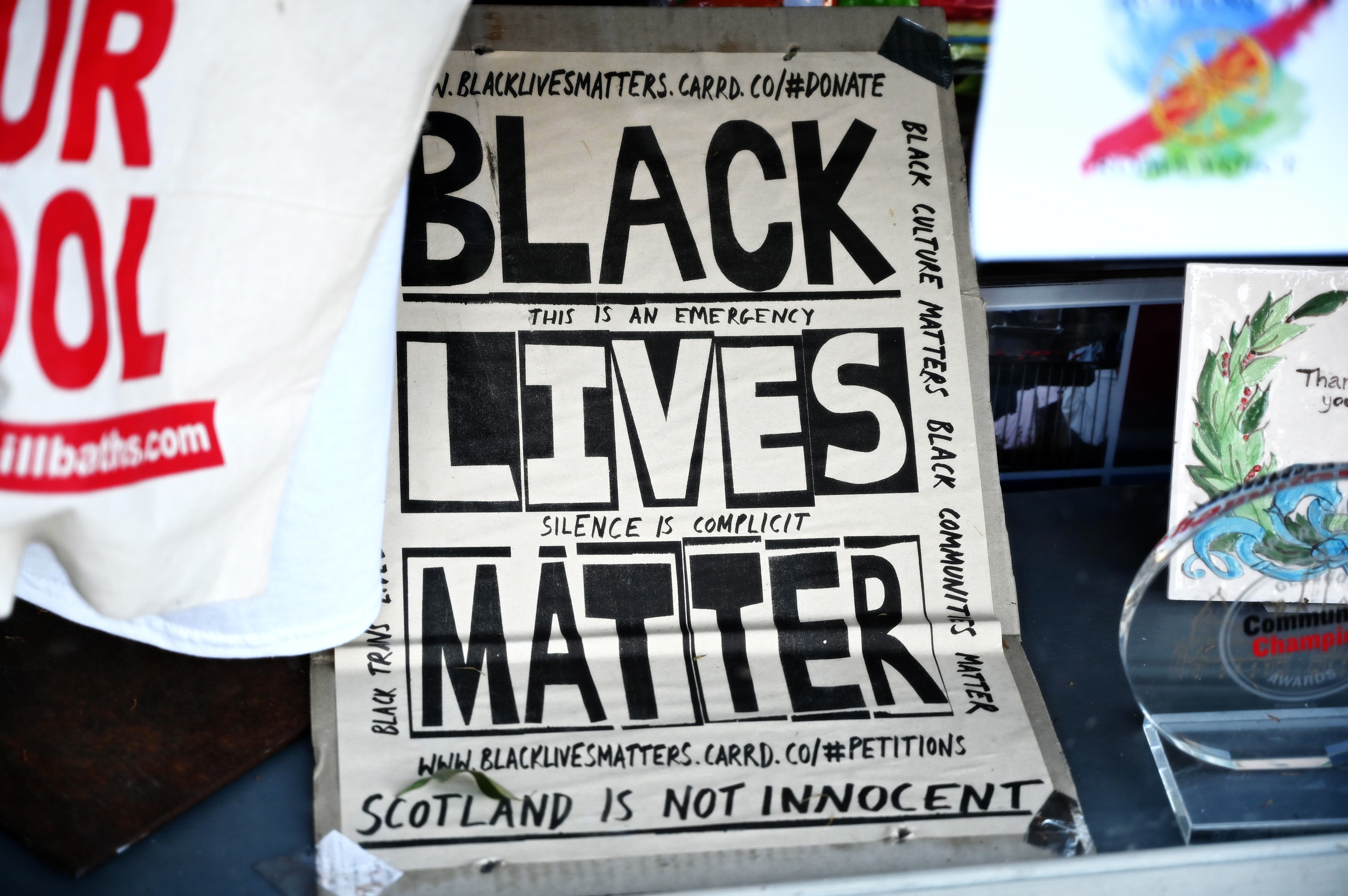

Scotland Isn’t Innocent

Examining a Country’s Silenced Past Amid an International Reckoning with Race

by Rory Pelella

When Dr. Myrtle Peterkin moved to Scotland in 1979 to pursue higher education at the University of Glasgow, one of the things that stood out to her was that the place names there closely resembled those in her home country of Guyana.

“Places like Inverness and Fyrish and Cromarty and Rosehall…I’m thinking, ‘Oh that’s interesting, we have these same names at home,’” said Peterkin, who grew up on a sugar plantation in Demerara and later became the first Black hematologist in Scotland.

“As I got to know more about the geography, I realized that many of these place names were in the Highlands, so there was clearly a link between the Highlands and my country,” Peterkin said.

It took Peterkin a few more years, however, before she finally began to understand this connection – one spanning 4,500 miles, from South America to the northernmost part of Great Britain — as something other than a coincidence. She learned the history behind those names is a complicated one, tainted by slavery and the transatlantic slave trade.

“During Black History Month, I went on this walking tour, which was advertised as a slavery walking tour,” Peterkin said. “That’s when I got my first concrete evidence that there was a very strong link between Scotland and the slave trade.

“Even though it was focused on Glasgow, it made me start to think that perhaps the place names had a lot to do with slave ownership and the trading of enslaved people,” she added.

The reason Peterkin hadn’t thought about this connection before, is because it was the antithesis of everything she learned growing up, at the end of the British colonial era. She said she was frequently exposed to a heavily biased narrative that everything British was best, and the people of Britain could do no wrong.

Later, when Peterkin moved to Scotland, a similar – but slightly more Scotland-centric –narrative was reinforced, particularly whenever it came to acknowledging the country’s past. It’s why she said she didn’t initially associate the place names she recognized with slavery; she was conditioned to think her adopted country was innocent.

“The story that Scottish people have firmly in their minds is that the English were the predominant people involved in the enslavement of people,” Peterkin said. “That is a widely held belief — that the Scots were not culpable.”

Peterkin also said she doesn’t need to travel far from where she lives to see this narrative in action.

In her neighborhood, for example, there’s a plot of land with several mansions, all of which were formerly owned by tobacco barons who made a living off the transatlantic slave trade.

While visitors frequently tour these homes and admire their beauty, Peterkin said that almost no one realizes that those who grew the tobacco, and thus generated enormous wealth for the barons and their mansions, were slaves.

“If you start telling the story of where the wealth was created, I think it would be very difficult for many people to come to terms with that,” Peterkin said.

She added that in Scottish museums, there’s little to no trace of “any reference to the slave trade or the enslavement of people.” Meanwhile, countless streets across Scotland are named after former slave owners or the ports and islands where their ships docked, which most people mindlessly walk past.

“We have Jamaica Street, India Street, Virginia Street, you name it,” Peterkin said. “They were trading with these places, but [many people think] ‘Oh, they were just trading.’

“It’s that kind of blindness that exists. That whole history has been silenced and it’s very difficult to overcome that.”

If not well-publicized, though, Scotland’s connection to and economic gain from the slave trade certainly is well-documented.

The Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery at the University College of London (UCL), for instance, has spent years tracing the impact of slave-ownership on the formation of modern Britain.

When slavery ended in 1834, the British government distributed £20 million to slave-owners as compensation for their “loss of property.” This created a national debt, which Peterkin said wasn’t paid off by taxpayers like herself until as recently as 2015.

An even closer look at those compensation records, however, shows that a disproportionately large share of that money was given to former slave owners from Scotland. In fact, one of the largest “single groups” of beneficiaries was Glasgow merchants, who accounted for 10 percent of all compensation directed toward British traders.

Meanwhile, Peterkin’s alma mater – the University of Glasgow – created a Historical Slavery Initiative to examine how the university, which was founded in 1451, and the city of Glasgow, benefited from slavery and the transatlantic trade.

David Duncan, the university’s chief operating officer and secretary, said a committee was founded back in 2016, after a group of historians approached the university’s senior management. The result of this subsequent investigation into the university’s links with slavery confirmed Peterkin’s findings.

Scotland was a relatively poor country until 1707, when it became part of the United Kingdom. Duncan said researchers concluded it was then that a lot of Scottish people became involved with trade with the developing British Empire and its colonies overseas. During the 18th and 19th centuries, Duncan said most of that trade revolved around tobacco, sugar, and cotton – all of which were crops produced from slave labor.

“A lot of merchants in Glasgow became very wealthy from that,” Duncan said. “Being on the west side of Scotland, they were pretty aggressive in getting involved in the transatlantic trade, and obviously a lot of that was based in plantations in the Caribbean and southern parts of the U.S.”

Duncan added that the wealth generated from the transatlantic trade and the lucrative shipbuilding industry it ignited, was then reinvested in the second phase of Britain’s industrial revolution. It helped fund railroads, factories, textile production, scientific discovery, technological innovation, and major institutions and universities.

At the University of Glasgow alone, researchers estimate just under £200 million of wealth was generated from sources tied to slavery, and/or the compensation payments made to former slave owners and their descendants.

“I think it’s important people know about this history that has been excluded from them, because it’s very clear that the society which we have at the moment, or the benefits which we enjoy today, would not be in place had it not been for the wealth that came into the country from the work and the labor of enslaved people,” Peterkin said. “[Those] revenues really fueled the development of so many things.”

And it wasn’t just industry and technology. Those revenues also fueled certain attitudes and narratives, particularly about the people responsible for making the profits – those of Afro-Caribbean descent.

“There are a lot of very difficult things one has to take into consideration in telling the story of where the wealth has come from, which brings us to the whole concept of racism,” Peterkin said.

“I think the reason racism continues to be a serious problem in Scotland is because the narrative has always been, ‘We are the superior race, we are the masters’ and to go even further than that, ‘People of color are of lesser intelligence, they are closer to animals.’”

Peterkin said the institution of slavery and the way in which the transatlantic slave trade operated only perpetuated these beliefs. The effect is still felt in society today.

“It’s ingrained in the psyche of the nation,” Peterkin said. “It’s very, very difficult to remove that reinforcement of subservience, of a lesser status.”

Despite the challenge, however, Peterkin and Duncan both said there is hope. This became particularly evident at the peak of the coronavirus pandemic in March 2020, after the police killing of George Floyd in the United States sparked an international reckoning with race.

“When Floyd was murdered, it affected everywhere in the world,” said Duncan. “[People] used it to highlight the issues they experienced. It was a catalyst.”

In Scotland, protestors took to the streets. Several activists emerged and contributed to the conversation about race in the country in unique ways.

One of those activists was Wezi Mhura, an artist who works in theater, dance and visual arts. Mhura moved to the United Kingdom from Malawi at the age of 12.

Mhura founded a Black Lives Matter mural trail in Edinburgh in June 2020, and soon expanded this project across all of Scotland.

“I was always very aware that the conversation around race in the United Kingdom tends to be London-centric or down-south-centric and the black Scottish voice was missing from that,” Mhura said. “What I wanted to do was lend my support to the Black Lives Matter movement and the conversation that was happening [by] highlighting black Scottish voices.”

Mhura chose the platform of art because she said she knew not everyone felt comfortable gathering in large groups to protest during the pandemic. She wanted to provide a space where people could participate in the movement without any risk to their health. At the time she came up with this idea, the government recommendation was that citizens were allowed to go out for a walk for one hour each day.

“What I thought was going to be very powerful was if within that one hour, you could meet public art on the outside of cultural institutions [that] would be the voice of this conversation,” Mhura said.

She said she reached out to multiple venues and asked them if they would lend their walls, doors, railings, and the sides of their buildings to local Black artists.

Then, Mhura commissioned those artists to paint murals, while giving them complete freedom over their work. All she asked is that they made some sort of statement about being Black and Scottish, and their experience of that, from whatever point of view they wanted to spotlight.

As a result, Mhura said the artwork took many shapes and forms and involved numerous conversations in more than 60 locations across Scotland. Many artists focused on the country’s connection to the slave trade. Others focused on themes of music, culture, health and medicine, immigration, and police brutality. Nothing was off limits.

“It was about having that multiple voice because [the movement] is about many things to many people,” Mhura said. “The nuances of systemic racism are embedded in so many different parts of society.”

But Mhura also made it very clear she didn’t want to dwell too much on the past. Instead, she said she wanted to empower a conversation about the present.

“As much as it’s a historic conversation of what happened in the past, it’s also a conversation about now and about how education doesn’t teach these things — how certain histories have been whitewashed,” Mhura said. “The conversations are very different, but they all speak to the fact that black lives matter.”

And in Mhura’s mind, this dialogue was long overdue. She, too, said the country is plagued by a narrative of innocence when it comes to slavery and race issues.

“I think because Scotland has never had slavery in its actual country, and because there was never any tension visible in the streets or race riots or protests like down south, it’s very easy for the Scottish population to feel distanced from that conversation,” Mhura said. “It’s difficult for some people to understand why there’s a need for [it].

That need was reinforced for Mhura, however, shortly after the project began. She said that several artworks involved in the Black Lives Matter mural trail were vandalized. Sometimes, this meant they were ripped or removed from the wall. Other times, people spat and threw things at them.

It was a clear sign to Mhura that much more work remains; conversations must continue to combat the narrative of Scottish innocence, which has been ingrained into society through the repetition of falsehoods.

But overall, Mhura said her experiences with the trail have been positive ones, which leave her feeling optimistic.

“One of the really important things that happened every single time we were putting an artwork up, is people would stop and have a conversation with you,” Mhura said. “Then you would explain what you were doing, and what would end up happening is people would begin to open up about misconceptions around race and other people.”

“Looking back on the last two years, there’s conversations I’ve had which I know I wouldn’t have been able to have five years ago,” Mhura said. “So, there has been a shift. It’s made people reexamine their own power structures.

“Not everybody is willing to have that conversation, and there’s still a lot of struggle that needs to happen, but there has been a sort of shift in the way that it now feels more acceptable to call out these situations.”

One of the most recent examples of this shift can be found all the way in the Caribbean, where campaigns are growing to severe ties with the royal family.

In fact, when Prince William and Kate Middleton arrived on the islands for a week-long visit on March 22, they were met with resistance and tension. The Royal Family canceled certain outings and appearances during the trip, as they faced protests in every country they visited.

In Jamaica, for example, academics, politicians, and other public figures signed an open petition in preparation for the visit, asking the British government to formally apologize for subjecting the country to colonial rule and slavery, and ultimately pay reparations to the people on the islands.

It’s exactly the conversation people like Peterkin have been waiting for. But for the renowned physician, it’s less about the money and more about the fact that people – particularly those responsible for perpetuating slavery – finally open their eyes to the consequences of these atrocities.

“I don’t know that you can repay that debt,” Peterkin said. “I just would like the British public to have an awareness of the contribution that enslaved labor has made to this society, and continues to make, because that money is still circulating. That money is still being used to do all kinds of things within this society. It’s going down from one generation to the other.

“We must now try to correct that, or to at least acknowledge that.”

4.30.2022