Life in the Gray Zone: Understanding Statelessness in Estonia

By Hunter Smith

TALLINN, Estonia – Konstantin Sviridovski is a man without a country. The 30-year-old was born and raised in Estonia, as were his parents and grandparents, but a tangled web of history, nationalism and government mandates has left him trapped in a legal gray zone.

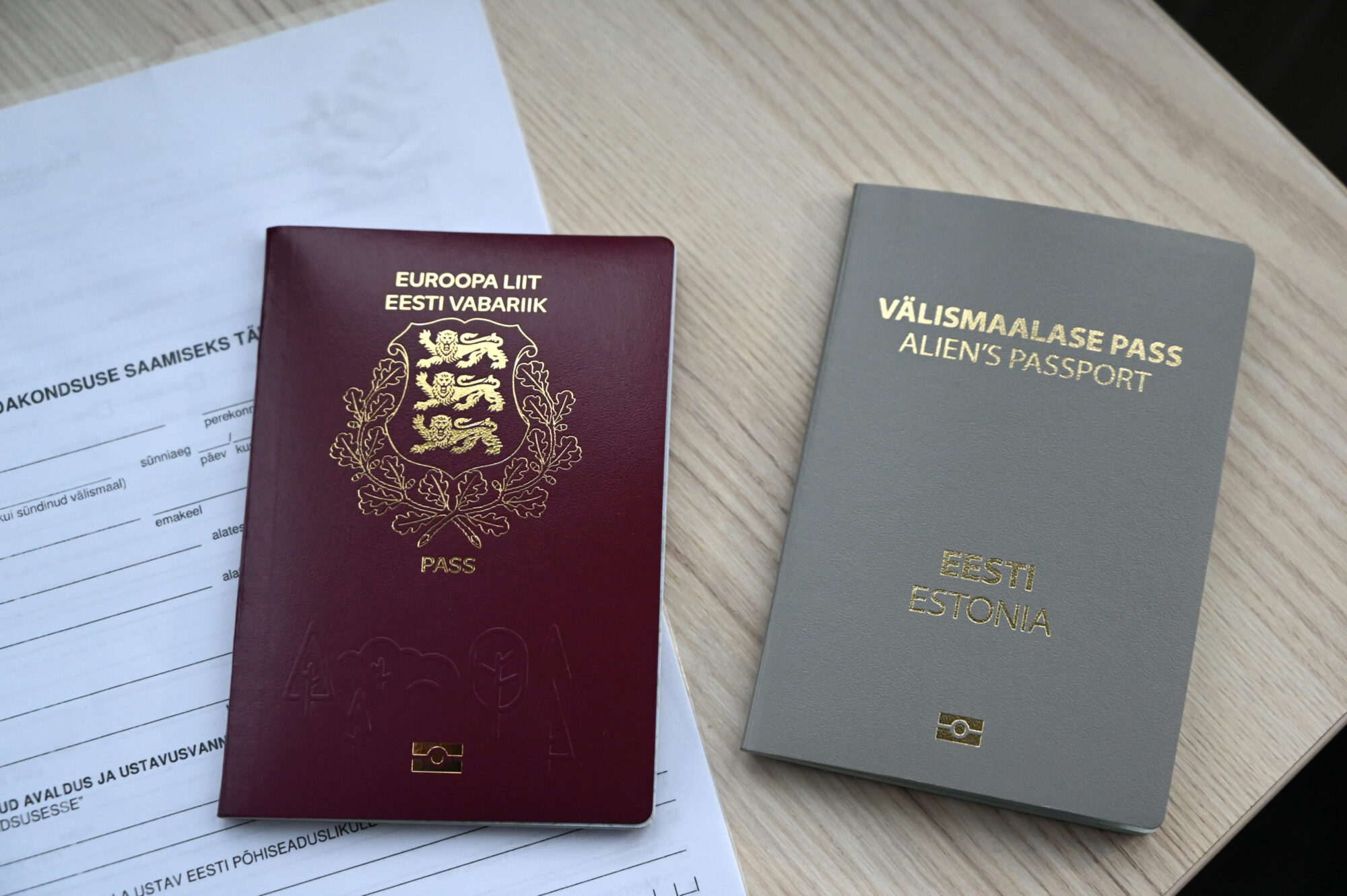

To underscore this reality, even his passport is gray, emblazoned with the words “Välismaalase Pass” meaning “Alien’s Passport” and inscribed with the proclamation that, “The holder of this alien’s passport is not a citizen of Estonia.”

Nearly 64,000 people in Estonia don’t have a nationality, making the country’s stateless population the world’s 10th largest. Some, like Sviridovski, have remained stateless by choice.

“For me to prove that I can be loyal to my country, to show that I can speak the Estonian language, it’s not a difficult task, but the question is, ‘Why must I?’” Sviridovski said.

The complicated history of Russians in Estonia

The answer lies in the complex history Estonia shares with its powerful next-door-neighbor—Russia.

Long dominated by foreign powers, Estonia, a modest nation of 1.3 million people, has a particularly painful history of occupation. Russia absorbed Estonia, first, as part of its empire in the 18th century until the war of independence in 1920 and then again after WWII, when Estonia became part of the Soviet Union.

During Estonia’s time as part of the USSR, one-fifth of the native population was lost to deportations, executions, and political exile. As part of the Kremlin’s policy of Russification, thousands of ethnic Russians were sent to live in Estonia and other occupied territories to spread Russian culture and language throughout the broader Soviet Union.

Estonia, like its Baltic neighbors, based its citizenship policies on the legal continuity of the pre-war Estonian Republic—granting citizenship in the new state only to people who (or whose parents) possessed Estonian citizenship before occupation began.

The new government forbade dual citizenship, forcing ethnic Russians to make a choice—either get a Russian passport, with no guarantee they could remain in Estonia or apply for Estonian citizenship, a demanding process that requires demonstration of a high degree of Estonian language proficiency. The only middle ground was to be classified as stateless and issued a gray passport.

“Estonians invented the so-called gray passport, which was supposed to be a temporary measure. But you know that temporary things… they sometimes get eternal,” said Yana Toom, member of European Parliament for Estonia.

Toom, 56, was born to ethnic Russian immigrant father while Estonia was still a Soviet Socialist Republic. After naturalizing in 2008, she joined the Estonian Centre Party, the only major party championing Russian-speaking minority rights.

According to Toom, back in 1992, a naturalization process didn’t exist in Estonia. Because of that, in the country’s first post-occupation election, the Riigikogu, Estonia’s parliament, was elected by only 28% of the population.

The nation was anxious to reverse years of Russification and limit Moscow’s influence over its territory, so they hurriedly adopted new requirements for Estonian citizenship, leaving nearly 500,000 people who were once citizens of the Soviet Union living in Estonia without a legal nationality. Making this decision before implementing naturalization procedures meant what was supposed to be a temporary measure turned into an enduring reality.

“Estonia is a national state… If I say that you are American. This is not about ethnicity, right? This is something very different. But in Estonia, if you say you’re Estonian, this is about ethnicity. This is not about citizenship,” Toom said.

Many Estonians remember vividly the hardships they experienced under Communist rule, imbuing a deep patriotism and particular sensitivity about protecting their national identity from extinction. When the country regained sovereignty in the early 1990s, the government attempted to undo Soviet era Russification by mandating the Estonian language in schools, certain occupations and government offices.

The government’s decision to not automatically extend citizenship to long-term residents of Estonia has been a provocative issue in the country’s domestic politics, as it highlights the deep contempt many Estonians have for Russia because of their experience under Soviet rule.

“I understand the fears of Estonians, but I also see the problems of Russian speakers. And this is my political mission, how I understand it,” said Toom, who has served in the European Parliament since 2014. “…If these national minorities are by the origin of former empires they are taken as a security risk.”

Toom herself chose the Estonian citizenship route, but she bristles at what she sees as the stigmatization of Russian speakers in Estonia. “I believe what the Estonian government is doing for years now, and what they continue to do, they are speaking about communist legacy about occupation and whatever and this is always a good excuse for continuing discriminating against people.”

Many Estonians consider statelessness in their country a non-issue, however stateless ethnic Russians consistently fare worse both economically and socially than Estonian citizens do.

According to Toom, stateless ethnic Russians experience the highest unemployment rate in Estonia and have for the past 30 years. The rate is consistently near double that of Estonian citizens, a study by the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees found.

That same study determined that 30% of Estonia’s prison population is comprised of non-citizens, despite accounting for only about 5% of the country’s total population.

While gray passport holders like Sviridovski can vote in local elections, they are unable to vote in national and European elections or hold office—leaving them powerless to improve their situation through political avenues.

In European Parliament, the number of representatives allotted to each country is based on population, not the number of citizens. The size of the stateless population of Estonia qualifies the country for an additional representative, yet they have no power to elect them.

Toom has made it her mission to represent the interests of stateless people. “I believe every time we speak about European citizens in Brussels we don’t speak about the color of their passport, we speak about people who consider themselves to be Europeans.”

A February 2022 study by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees found that 56% of the stateless population want Estonian citizenship, however the Estonian government maintains that the stateless population persists because they choose not to pursue naturalization despite the support the government offers to help them achieve it.

The communications advisor of the Estonian Ministry of the Interior, Mari Tupits, says despite the Estonian government’s efforts to reduce the number of stateless people, which includes simplified naturalization procedures and language and citizenship courses, many make the choice to not take advantage of the resources.

Tupits says the privilege of traveling visa-free to Russia and the ability to claim Russian army pensions are major factors. Other non-citizens, she says, “are socially uncapable because of their past, upbringing, addiction, mental state or mentality.”

Estonian language proficiency as a barrier to naturalization

However, some critics argue that the requirements for citizenship are too strict and pose barriers to integration, particularly for older or less educated individuals.

“My relatives don’t want to take Estonian citizenship. For only one reason, because they need to study the Estonian language, to pass the Estonian language exam. They don’t know perfectly enough the language to pass that exam. But for living, it’s enough,” Sviridovski said.

For many Russian speakers, the subsidized languages classes are an inadequate solution for addressing the difficulty and time-consuming process of achieving the necessary language proficiency.

According to Ly Leedu, an Estonian language instructor at Multilingua, the largest adult language learning school in Estonia. The Estonian language is part of the Finno-Ugric branch of the Uralic language family, meaning it is substantially different from the more prevalent Slavic, Romance and Nordic languages of the rest of Europe.

For most stateless ethnic Russians, their sole language is Russian. According to Leedu, it would take require over 220 academic hours of classroom study plus independent work to achieve the necessary level of proficiency for naturalization.

The Russian immigrant element that came to the country during Soviet occupation generally saw little need to learn Estonian or identify with the native people, which has made it difficult for many ethnic Russians to pass the language exam needed to obtain citizenship today.

Cheap shopping and avoiding conscription

While for many stateless people, particularly the elderly, stringent language requirements have prevented them from naturalizing, some have chosen to retain their gray passports for other reasons.

“For me there were only two things, you don’t need to serve in the military, and you had cheap shopping,” Sviridovski said.

In Estonia all physically and mentally healthy male citizens must serve in the Defense Forces. For men like Sviridovski, avoiding the otherwise mandatory 8 to 11-month conscription made the occasional drawbacks of holding a gray passport worthwhile.

Many stateless individuals felt as if their legal status rarely impacted their daily lives. Therefore, their decision to keep or reject it is based on a simple cost-benefit analysis.

Narva, the industrial hub in northeastern Estonia, is the E.U.’s most ethnically Russian city. For the massive stateless population there, crossing the border to Russia to buy groceries and other goods was a common practice.

Sviridovski said that when he got married in 2016, he went to Russia, to the town of Pskov, to purchase wedding rings because they were much cheaper there compared to Estonia. He could buy two wedding rings for 300 euros in Pskov; in Estonia they would cost him 1,000 euros, he said.

“Any types of items or products were two… three times cheaper in Russia,” Sviridovski said. “That practice continued in Estonia for many years. And right now, it just doesn’t give you the same profit.”

The start of the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine has largely eliminated the economic incentive to travel to Russia. “It doesn’t give me any benefits anymore,” said Sviridovski who cited this as the main reason he is now, after 30 years, pursuing an Estonian citizenship.

Ideological protest

Others, like Artjom Barsegan, a 30-year-old IT professional and friend of Sviridovski, have chosen to remain stateless for ideological reasons.

“I didn’t like the approach the Estonian government took a lot of years ago on how they acted in terms of making Russians learn Estonian,” Barsegan said. “Why should I invest, so to say, into Estonia to that extent? It’s more or less a protest because of how Estonia treated people.”

Despite his frustration with the Estonian government, he understands why people are afraid and lash out.

“I explain it as like a basic need of people to kind of feel angry towards someone” Barsegan said. “Unfortunately, they don’t understand that hatred makes hatred right. But yet again, they have the right to be afraid to be aggressive because of the previous historical stuff that happened.”

Toom explains that hatred is an expression of the “toxic political culture in Estonia” that impacts not only Russian speakers, but all minorities, particularly LGBTQ+ people. “We live in turbulent times you know, and people are really scared here. I know many Estonians who are really afraid of a Russian invasion. And if people are scared, they are not very rational,” she said.

~April 25, 2023

***

An earlier version of this story misstated Toom’s family heritage. Only her father is of Russian descent. Toom, her mother and her children were born in Estonia. A statistic about the unemployment rate of Estonia’s non-citizens was misattributed to Toom. It came from the UNHCR report titled “Mapping Statelessness in Estonia.”