Working three jobs in NewYork City, Ann O’Shea never thought she would find herself unemployed.

During the week O’Shea worked at Woodside Café as a waitress near her home in Queens. She bartended at various locations in Manhattan on the weekends. But, as shelter-in-place measures ravaged the country, O’Shea’s three jobs were ripped away from her in the span of one day.

“Where is my money supposed to come from? How am I supposed to pay my bills?” O’Shea said. “I’m scared like anyone else.”

O’Shea moved to New York 30 years ago from Ireland, where her entire family still lives. She had planned to return to Ireland in June — as she does every year — but she is now coming to terms with the reality that the COVID-19 pandemic might take her family visit, as well.

Over in Ireland, O’Shea said the country is taking similar precautions to the rest of the world to “flatten the curve.” Everyone is encouraged to social distance, non-essential businesses are closed and anyone over the age of 70 is encouraged to “cocoon,” or stay at home under all circumstances.

Emma McShane lives in County Louth in northeastern Ireland. When she compares her home country to the United States, she sees a difference in how Ireland is handling the pandemic.

McShane graduated from National University of Ireland Galway in 2019 with a bachelor of honors degree in psychological studies and philosophy. She is currently taking a gap year before pursuing her master’s in psychology. In late March, as rumbles of quarantine orders became serious, McShane decided to take a last-minute trip to visit her boyfriend in York, Pennsylvania, before Ireland’s travel advisories went into effect.

McShane said entering the United States was much more hectic than returning to Ireland two weeks later.

In American customs in the Dublin Airport, McShane went through two interviews before she was allowed to board the plane. In the first, authorities questioned her on other recent travels outside of Ireland. The second interview consisted of a temperature and physical symptoms check. McShane said she was in the airport for a total of nine hours before her plane took off.

“But, coming home it was so easy.” McShane said. “When I got back to Ireland I was handed a leaflet that told me to quarantine for 14 days, and I took my bag and left.”

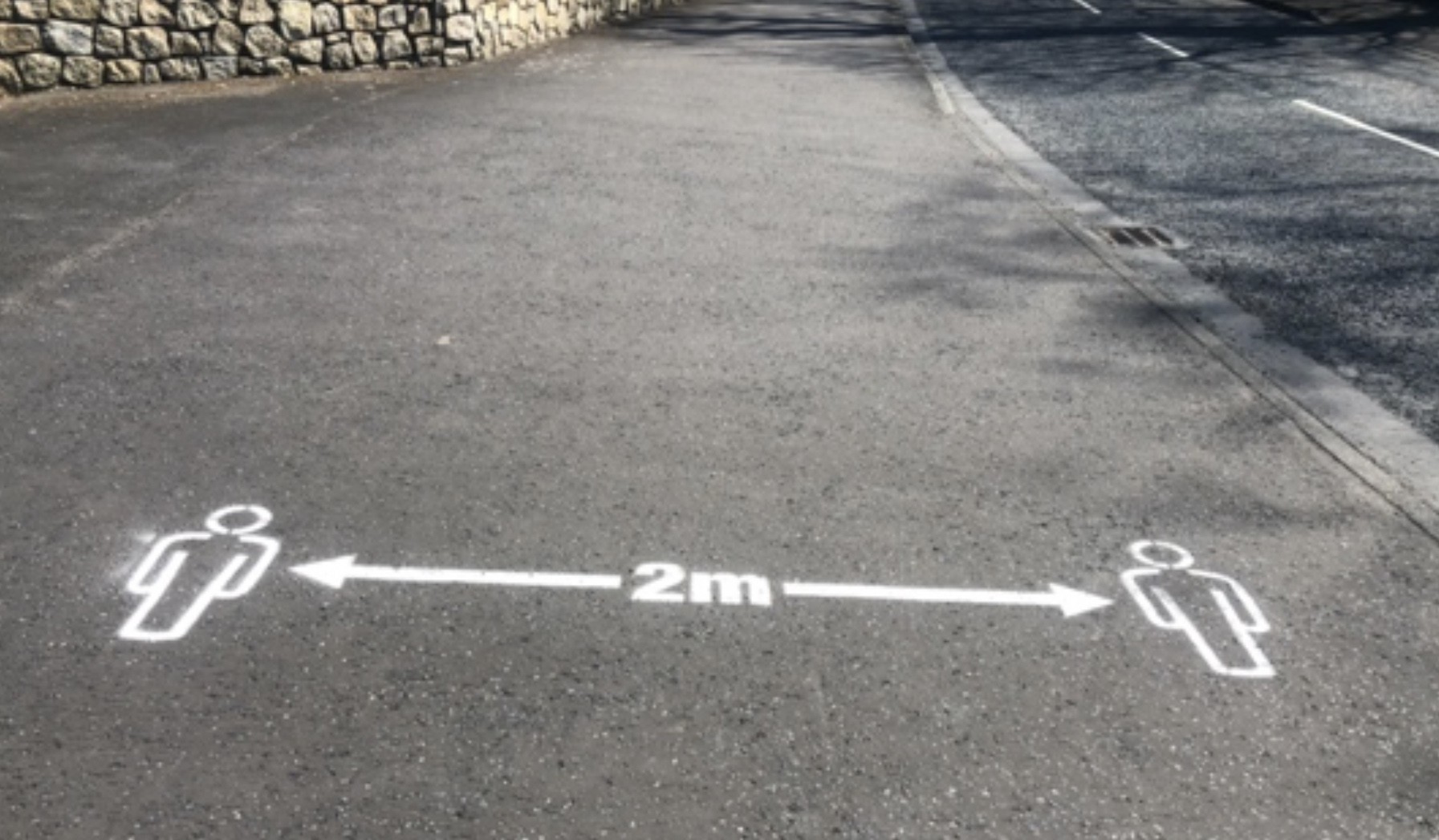

McShane said the Irish have become steadily more diligent in practicing COVID-19 measures. As she settled in back home, McShane said she first noticed people taking the situation seriously when pubs were advised to close down on March 15 — two days before Saint Patrick’s Day. Later on March 27, Prime Minister Leo Varadkar, who is also a physician, announced that no one was allowed to go more than two kilometers beyond home for non-essential reasons.

According to the Irish Mirror, thousands of Gardaí — Ireland’s police officers — have been working various checkpoints to enforce the new two-kilometer law. On April 15, the Irish Times reported a man named Denis Constantin was the first to be legally charged for violating the two kilometer limit.

“I was on a jog the other night and I was passing [a Gardaí] car,” McShane said. “I wanted to stop jogging but I thought, ‘Nope. If I stop jogging they’re going to think I’m out for another reason.’ So that’s what pushed me to keep jogging.”

Yet even under such a watchful eye, McShane said levels of fear are still notably lower than what she saw in the United States.

“It’s very chill here. If you’re going to compare the two, no one is living in fear here. While when we were in shops [in the United States], it seemed like people were genuinely scared,” McShane said.

She said that “panic shoppers” who hoarded groceries was a short-lived trend in Ireland, lasting only a day or two. McShane said she thinks American media is to blame for the increased panic on this side of the Atlantic Ocean.

“Every time the news came on when I was over there I was like, ‘Turn this junk off,’” McShane said. “They use scare mongering tactics to really panic the people. They were almost encouraging this greed attitude.”

Kelly Fincham said she has seen a similar trend. Fincham is an associate professor of journalism at Hofstra University. She lives and works in New York with her husband, but returned to Drogheda, Ireland, in December when her mother became ill. She remains there today.

Fincham said she sees a more concerted national effort to combat the coronavirus in Ireland than in other countries — specifically the United States and the United Kingdom.

“I say you have famine memory in Ireland, you probably also have a country that’s spent 800 years trying to get the British to leave,” Fincham said. “So, maybe there’s more cohesion here around a shared goal.”

Before she became a professor, Fincham was an associate editor of the Irish Independent. She agrees that the big difference between U.S. and Irish reaction to Covid-19 is the media. There are no Murdoch News Corporation tabloid-style type of publications in Ireland as there are in the United States and the United Kingdom.

“I think where you see these real issues start to emerge is in countries where you’ve got that polarizing press environment,” Fincham said.

McShane said the Irish government and news outlets are constantly posting positive stories such as how many people recovered in a week, while at the same time encouraging everyone to stay inside.

“It feels like a community,” McShane said. “If you’ve got Fox telling people that there’s no need to panic, no need to worry, that’s an issue,” Fincham said.

American cable news channel Fox News has been under scrutiny recently for how it has handled its coronavirus reporting.

“Maybe it’s because the country is so small it wouldn’t sustain anything, but you wouldn’t have what’s been going on with Fox in Ireland,” Fincham said.

Aside from the media, Fincham said social welfare nets in Ireland are working to relieve people’s fear, specifically noting the differences in Ireland’s healthcare and unemployment benefits systems.

“For me what this virus is really revealing is your country is only as strong as the weakest people in it,” Fincham said. “I would be very concerned about what will happen in America. If they’re on minimum wage or they’re getting unemployment and they don’t have healthcare … what happens next?”

O’Shea’s answer?

“What do you do?” O’Shea asked. “You sit in your home and look out your window and just hope for the best.”