The Tree of Life synagogue mass shooting raises questions about the death penalty.

The morning of October 27, 2018, was not a normal one for Arlene Wolk.

It was Saturday, and she wasn’t feeling particularly well. After waking up throughout the night, she was “extremely tired” and decided to do something she normally didn’t do — sleep in.

Sleeping in didn’t just mean getting extra rest. It meant missing Shabbat services, which she had attended often at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh for more than 20 years.

Though the “regularly active” congregant didn’t like to miss these traditions, she decided it was probably best if she stayed home. So, she went back to sleep.

Arlene Wolk wasn't feeling well October 27, 2018 so she didn't attend Saturday morning services at the Tree of Life Synagogue that day when a gunman opened fire and killed 11 members of the congregation. ~ photo by John Beale

Now, over one year later, Wolk is still reckoning with that decision to stay home. Little did she know it would save her from being in the center of the deadliest anti-Semitic hate crime in American history.

At 9:50 a.m. that Saturday, 11 worshippers at the Squirrel Hill neighborhood’s Tree of Life synagogue were shot and killed when Robert Bowers, an anti-Semitic white nationalist, entered the synagogue with an AR-15 and three Glock .357 handguns, opening fire as he declared his mission to “kill Jews.”

Wolk’s sleep was eventually interrupted by a call from a family member — a cousin who lives in Maryland but who grew up in Squirrel Hill attending Tree of Life. She was in tears, wondering if Wolk was alive and safe.

Wolk went immediately to her computer and then to her television. The Tree of Life was all over the news.

“You couldn’t leave your home, you couldn’t walk, you couldn’t drive… The police and the FBI didn’t know if there were multiple shooters, if it was a terrorist attack, or what was going on,” Wolk said. “It felt like a war zone.”

***

Bowers was originally indicted on 44 federal charges, which eventually grew to over 60 charges, including 11 hate crimes resulting in death and eight counts of attempted murder.

In a statement released three days after the shooting, Allegheny County District Attorney Stephen Zappala stated that in his experience, Bowers’ case was “clearly a capital case.”

Further, his statement noted that local and federal law enforcement started off working together, but it had transitioned into an investigation by the FBI and Department of Justice.

“While we are confident that we can move forward with our prosecution, as a practical matter, the circumstances indicate that it is prudent to allow this case to proceed at the federal level at this time,” the statement read.

One day later, Scott Brady, U.S. attorney for the Western District of Pennsylvania, said in a statement that pursuing the death penalty could help seek justice for the victims of the shooting as well as healing for “victims’ families, the Jewish community and our city.”

“Our office will spare no resource, and will work with professionalism, integrity and diligence, in a way that honors the memories of the victims,” Brady said. “This is what the public expects from the U.S. Department of Justice. And truly we, as Pittsburghers, can do no other. It is time to go to work.”

It wasn’t until late August that federal prosecutors officially announced they would seek the death penalty for Bowers.

Not everyone victimized by the tragedy agrees with that decision.

The Tree of Life Synagogue in the Squirrel Hill section of Pittsburgh. ~ photo by John Beale

Three congregations were housed in the Tree of Life synagogue — Tree of Life – (Or L’Simcha), located on the main floor; New Light, in the basement; and Dor Hadash on the top floor.

Bowers ambushed all three floors. But the congregations themselves, in statements or comments from individual members, have voiced different views on the pursuit of the death penalty for Bowers.

Congregation Dor Hadash released a statement that said it opposes Bowers receiving capital punishment. Individual members within Congregation Dor Hadash released statements echoing that sentiment.

New Light did not release a statement as a congregation, but some individual leaders did. Rabbi Jonathan Perlman wrote a letter to U.S. Attorney General William Barr in an attempt to talk him out of pursuing the death penalty.

“I want to report to you as a victim of the attack and one who has spoken to our families that we have been depleted by the ordeal of this year… You and I know that the U.S. Justice Department has not implemented the death penalty in 18 years. Following many countries around the world, I would like to believe our nation is slowly phasing out this cruel form of justice.”

Perlman said that Judaism “vigorously” opposes the death penalty.

Rabbi Jeffrey Myers of the Tree of Life congregation has declined to comment on what punishment prosecutors should pursue.

In mid-October, federal prosecutors rejected Bowers’ offer to plead guilty in exchange for a life sentence without any possibility of release. Some individuals within the Tree of Life synagogue community spoke out in opposition to that decision.

Stephen Cohen, co-president of New Light Congregation, said he is not against the death penalty, but he does not want Bowers to receive the death penalty. He wrote a letter in August to the U.S. attorney general, saying he hoped federal prosecutors would accept the offer of a plea deal for Bowers to spend his life in jail. His argument, he told local Pittsburgh news station KDKA, is that since witnesses wouldn’t have to testify, victims could avoid taking on potentially new traumas of being in a courtroom and having to relive the shooting.

“By going for the death penalty, it could be 10 years or more before we reach closure,” Cohen said. “That’s just cruel.”

Judah Samet, a Holocaust survivor who worshipped at the Tree of Life synagogue, told USA Today days after the shooting that the only reason he wasn’t in the synagogue when Bowers started shooting was because he got caught up in conversation with his housekeeper.

“It could heal the public knowing that he’s gone,” Samet said to KDKA. “I think that’s why the government wants to kill him.”

However, Samet said to USA Today that he does not want to see Bowers receive capital punishment, noting that he believes a death sentence would let Bowers off easily. He also said that he was OK with a trial but that he ultimately wants Bowers to spend life in jail.

“I don’t want to kill because, to me, it would be a gift to him,” he said. “He won’t suffer.”

Fence along the outside of the Tree of Life Synagogue. ~ photo by John Beale

***

Though Perlman said Judaism “vigorously opposes” capital punishment, Rabbi Ira Dounn, from Highland Park, New Jersey, doesn’t quite see the relationship between their religion and capital punishment as all that black and white.

Dounn said there is an undeniable history behind Judaism and the death penalty — In the Torah, it serves as punishment for murder, adultery, the “wayward and rebellious son,” breaking the Sabbath and several other wrongdoings. He also referenced the hanging of Adolf Eichmann, a leading architect of the Holocaust, in Israel in 1962.

However, Dunn said that Judaism, Jewish law and the modern state of Israel have been very hesitant to enforce the death penalty. Though capital punishment is legal in Israel, no one else has been executed there since Eichmann.

“In the context of Tree of Life, this is pretty interesting, actually,” Dounn said. “Like many things in Judaism, if you ask different rabbis, you’ll get different answers.”

Dounn brought up the idea of Judaism as a religion that’s especially open to letting worshippers interpret things for themselves from “a vast compilation of sources.” He said that the freedom to conclude, or not conclude, can create a normal, common trend of Jewish practice that might differ from what exactly the Torah might say.

Dounn noted similarities between the circumstances of Eichmann’s case and the Tree of Life shooting.

“[The Eichmann trial was] a case of terrible anti-Semitism and genocide, and this is a terrible situation of anti-Semitism and massive atrocity,” Dounn said. “It’s complicated. Some people don’t think it’s so complicated, but I think if I were to try to be fair to every view point, I’m just wary to saying Judaism or Jewish law says ‘this,’ when obviously there are dissenting opinions.”

While he said he doesn’t feel at liberty to speak for the entire Jewish community, and “defers to the victims and their wishes,” Dounn does personally see Bowers’ actions as permissible for receiving the death penalty in the United States. Despite that, he said he’s not sure that administering the death penalty to Bowers is what the punishment needs to be.

“For the 11 people who died at the Tree of Life synagogue last year, they can’t get their lives back. And their families who were all affected because someone in their family got murdered, they can’t have their lives back,” Dounn said. “It’s really reasonable to be really angry. I think Bowers should serve the rest of his life in jail. Whether or not he should be executed… I don’t feel strongly that that [should be] his punishment.”

***

Robert Dunham, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, said unintended but common side effects of seeking the death penalty for a suspect are the emotional wounds that can be reopened for family members, communities and loved ones of murder victims. As Perlman expressed in his letter, that factor in itself can be enough for those severely impacted by a hate crime, such as the Tree of Life shooting, to be anti-capital punishment.

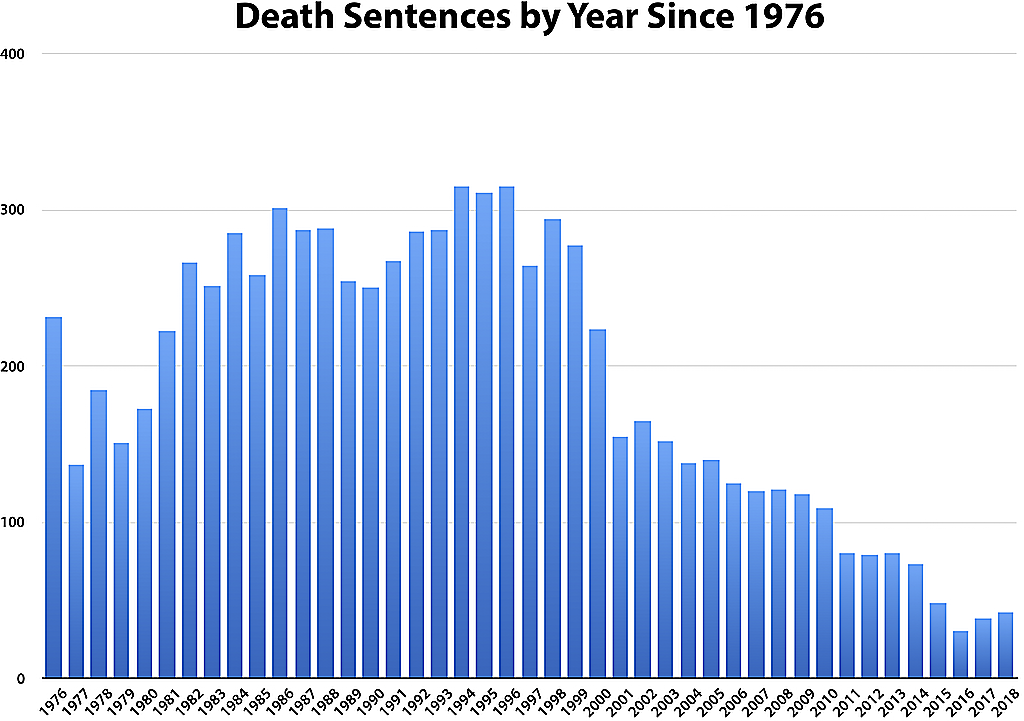

Dunham said that mass murders certainly qualify as “the worst of the worst” type of murders, for which the death penalty is supposed to be reserved. Historically, though, many cases may have not ended with a death sentence being imposed.

“Hate crimes are an attack on a community, and that means that trying [the suspect] can re-traumatize the affected community,” Dunham said. “That’s a powerful reason to just end the case, because a life sentence will end the case, and people can get on with healing.”

Across the United States, 29 states permit capital punishment and 21 don’t. However, four of those 29 death-penalty states — California, Colorado, Oregon and Pennsylvania — have moratoriums on carrying out executions.

Pennsylvania, with 154 inmates on death row, is second only to California, with 740, as the state with the highest number of inmates on death row.

Even before Democratic Gov. Tom Wolf put the moratorium on Pennsylvania’s death penalty in February 2015, Pennsylvania had executed just three individuals since 1962: Keith Zettlemoyer, Leon Moser and Gary Heidnik, all during the two terms of Republican Gov. Tom Ridge, whose 1994 campaign promised to strengthen anti-crime measures.

Zettlemoyer murdered a male friend, Moser murdered his estranged wife and two daughters and Heidnik murdered two of six women he kidnapped and tortured in his home.

Dunham said it’s not “unusual” for capital cases to take many years. And in the case of mass shootings, he said there is often an enormous amount of evidence to sort through, potentially dozens or hundreds of witnesses to hear from and pretrial hearings related to the mental capacities of the defendant to schedule.

The last time a federal execution took place was in March 2003 for Louis Jones Jr. — a U.S. Gulf War veteran who kidnapped, raped and murdered a 19-year-old soldier named Tracie McBride.

Regarding mass murders that shook national news, the last assailant to be executed by the federal government was Timothy McVeigh, who was convicted of carrying out the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing that killed 168, including 19 children. He was put to death on June 11, 2001.

Dunham pointed to other cases like the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting in Parkland, Florida, in 2018, where local prosecutors are seeking the death penalty Nikolas Cruz, the then 19-year-old the assailant accused of killing 17 people and injuring 17 more.

Dunham said the prosecution in that case plans to present more than 100 witnesses. Each of them, including children and young adults, needs to be interviewed, thousands and thousands of pages of documents need to be reviewed and there’s likely going to be “significant mental health evidence” that could result in pretrial hearings related to the mental competency of Cruz.

And even then, if strong enough mitigating evidence about his mental health works in his favor, Cruz still might not be sentenced to death, Dunham said.

In many mass shootings, assailants have not made it out of their attacks alive to even stand trial. In fact, suspects in nine of the 10 deadliest U.S. mass shootings to date died either by police or by suicide.

Some of those deaths include Stephen Paddock, 64, who police believe died by suicide after killing 58 people and injuring nearly 700 concert-goers in October 2017 from a hotel room overlooking Las Vegas’ Route 91 Harvest festival; Omar Saddiqui Mateen, 29, who was killed by police after he shot and killed 49 and left over 50 injured in June 2016 at Pulse, a gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida; and Seung-Hui Cho, a 23-year-old Virginia Tech student who died by suicide in April 2007 after killing 32 and wounding an undetermined number of people on campus.

Among the assailants in recent cases who have lived to stand trial is Patrick Crusius, the shooter who said he targeted Mexicans in August 2019 when he killed 22 people at an El Paso, Texas Walmart. At the state level, Crusius was indicted by a grand jury in September for capital murder charges — the highest charge in the state of Texas, which is punishable by the death or life in prison with no chance of parole. The Department of Justice called the attack an act of domestic terrorism, and federal authorities are still looking into potential hate crime charges, National Public Radio reported in October.

Another is Dimitrios Pagourtzis, who was charged with capital murder by the state of Texas for the May 2018 El Paso High School shooting. He was 17 years old when he was charged with killing 10 people and wounding 10 more. Because he was a minor, Pagourtzis is exempt from the possibility of receiving capital punishment by the state of Texas. His trial is set to take place in January.

***

More than a year has gone by since Robert Bowers entered the Tree of Life in Pittsburgh. That horrible day remains vivid in the mind of Arlene Wolk.

Arlene Wolk holds a prayer book at her home. ~ photo by John Beale

She said she was flooded with calls from fellow Pittsburghers whom she hadn’t heard from in years, as well as people she knew from across the country. They all said they saw an attack at her synagogue on the news and wanted to see if she was safe.

Wolk’s mind was spinning, as she learned at first that eight people were killed and then three more were confirmed dead. Officials announced that they would not release the names of the deceased until 9 a.m. the following day.

“I had a really sleepless night, because I knew for sure that this was a matter of ‘Which ones am I going to know? Who didn’t make it?’” Wolk said. “So the next morning when they read the names… it was just the worst day of my life.”

Of those 11 congregants, six were individuals Wolk regularly worshipped with. She was especially close to brothers Cecil and David Rosenthal, 59 and 54, and Rose Mallinger, a 97-year-old congregant she saw “five or six mornings a week.”

Wolk and Mallinger would walk home from the synagogue together, since they both only lived a few blocks away.

Wolk said certain parts of her life aren’t the same anymore, and she’s not so sure they will be ever again.

She said she still takes time to worship — but not five blocks down the street anymore. Since the Tree of Life synagogue is closed, many other Pittsburgh congregations have opened their doors to those who don’t have a synagogue to call “home” anymore.

Wolk has settled in temporarily at Rodef Shalom, a major Pittsburgh congregation with a synagogue in the Oakland neighborhood.

Wolk said she is “quite liberal” in many areas of her life, and she said she was never much of a proponent for criminals receiving the death penalty. Her perspective began to change slightly as the number of mass shootings climbed over the past decade.

Once a mass shooting came to her doorstep, things changed even more.

“I used to say, ‘Oh, well, you know, everybody needs forgiveness,’” Wolk said. “Not this time. Not this time, because the shooter knew what he was doing. He planned very carefully on that morning, and he went on all three floors, anywhere he heard any noises. Anybody praying, he was there.”

Wolk said she feels that “justice really needs to be served in this case.”

She’s open to the fact that while all three congregations endured loss caused by the Tree of Life shooting together, worshippers can disagree on what should be the penalty for Bowers if he is convicted.

After Rabbi Perlman publicly shared his letter to the attorney general, Wolk felt compelled to write him a letter expressing her thoughts in favor of Bowers being executed.

Wolk said she certainly can understand Perlman’s perspective, but she stands strong in her opinion on Bowers receiving capital punishment since “[the shooting] happened the way it did.”

“I’ve thought a lot about it… I understand that [Perlman] and others who were there that day don’t want to relive the trauma,” Wolk said. “But it’s clear [Bowers] is guilty, and that’s why I’m speaking out about it. If I weren’t so personally affected, it might be different. But this really hit me extremely hard.”

***

For Wolk, October 27, 2019, was a day of remembrance — not that a day has gone by since the attack where she hasn’t thought of Mallinger, Jerry Rabinowitz, the Rosenthal brothers, Daniel Stein, Richard Gottfried, Joyce Fienberg, Melvin Wax, Bernice and Sylvan Simon and Irving Younger.

She’s felt moments of comfort, such as when worshippers from Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church — the South Carolina church where white supremacist Dylann Roof killed nine black worshippers at a Bible study in 2015 — visited the Tree of Life synagogue community in May and shared their experiences on moving past tragedy.

Now, in Wolk’s backyard, there is a 6-month-old hydrangea bush. Whether it’s wilting, as it is now with winter approaching, or this past spring, when it was blooming, there have always been 11 flowers.

“Eleven people were killed,” she said, “and I think of them every day.”

~ 11.29.2019