Agriculture and urban growth have degraded water quality in the Chesapeake Bay, the largest estuary in North America.

The Virginia shore of the Chesapeake Bay ~ photo by Tommy Alger

Rock Hall, Maryland –There was a time when this tiny Eastern Shore community of 1,300 was a thriving, commercial water town, its docks full and nearly every resident in some way or another impacted by the well-being of the Chesapeake Bay and the fish, clams, oysters and crabs coming fresh out of its waters.

In the 1970s there were 132 boats out of Rock Hall every day, Town Manager Ronald Fithian said. He isn’t sure if there is one full time oyster boat today.

“I can see a difference, as a waterman, locally,” Rock Hall councilman and waterman Brian Nesspor added, sitting across from Fithian recently inside the town hall.

As a 12-year-old, Nesspor started working for fishing parties, often learning about the bay and working with family before becoming a full time fisher and crabber.

Fithian recalled when he could make $50 after school at the docks. He, too, went straight to the water after graduating from high school in 1969, fishing, crabbing and harvesting shellfish, depending on the season.

Those times now are a happy memory, the local men say. People can’t afford to store or dock their boats any longer, so they come in solely on the weekends, Nesspor said. People will boat across the bay for the day or drive in with their boats on trailers.

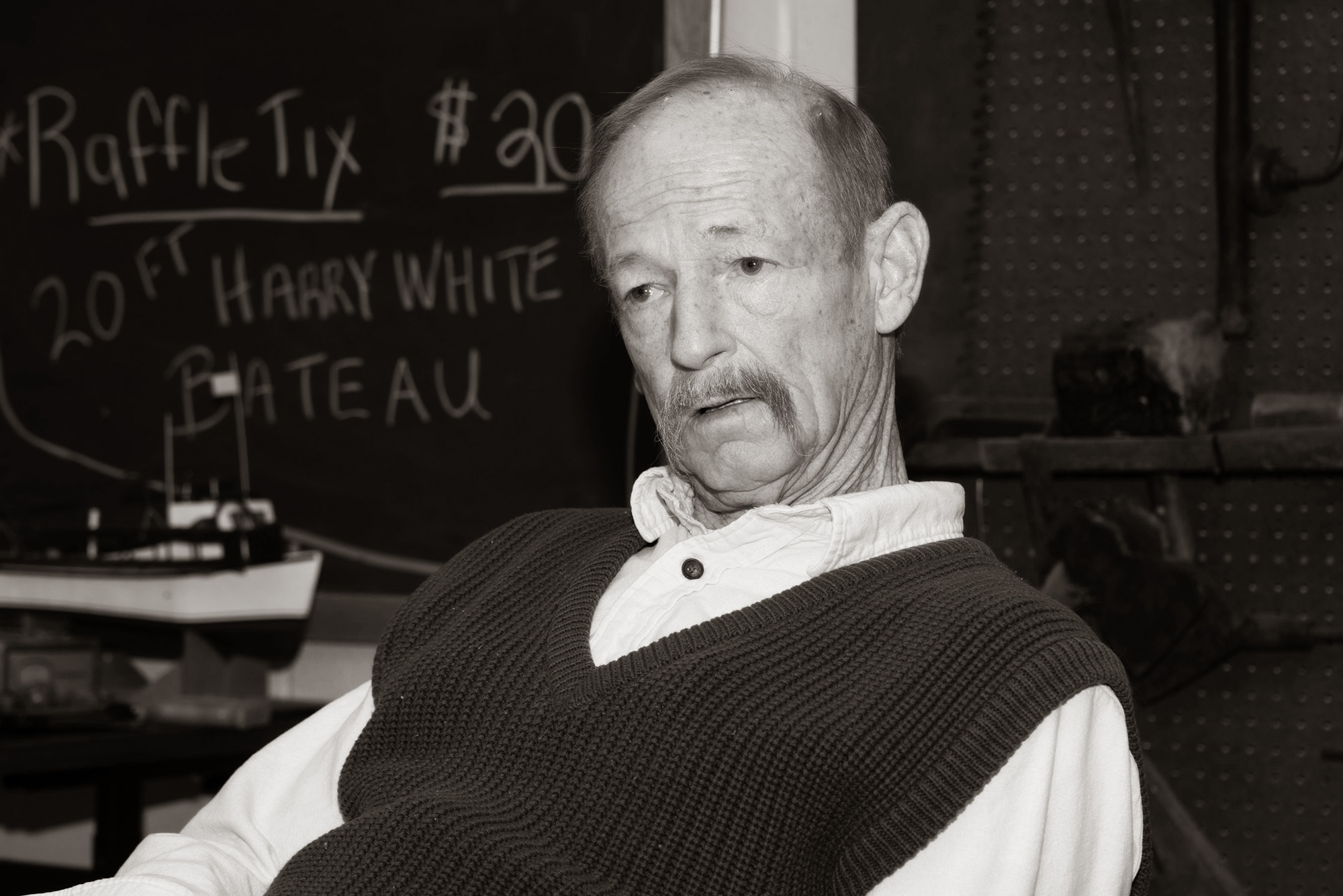

“It’s been a lot of changes…. We’re changing from a work town to a play town,” said local waterman Scratch Ashley. “When I started, my oyster license was $10. When I quit, it was $310.”

The Chesapeake Bay has changed, and much of the change is because of what’s happened and is continuing to happen on the land surrounding one of the country’s most recognizable natural resources.

“Humans have not figured out how to live on the land without messing it up,” said Nicholas DiPasquale, director of the Chesapeake Bay Program, an Annapolis, Maryland, partnership of scientists and others who have been working since 1983 to help restore the waterway. “Nature is always attempting to seek a balance, but humans are notorious for messing it up.”

The health of the Chesapeake Bay, the source of some 500 million pounds of seafood harvested annually from its waters, has been a concern for many decades. But within the last 30 years those concerns have become more focused on a growing population’s impact on the bay, its ecological state and the impact on wildlife.

For those whose life’s work focuses on the Chesapeake Bay, this past year has been one of the evaluation years in a long-range plan by the Chesapeake Bay Program to “advance restoration and protection of the Chesapeake Bay ecosystem and its watershed” by 2025.

In part, the watershed agreement lists 10 principal goals, including creating sustainable blue crab, oyster and fish populations, protecting the land and water habitats, reducing pollutants and supporting land conservation efforts.

Wildlife populations in the bay are vulnerable to water pollution and habitat loss. ~ photo by Tommy Alger

****

The Chesapeake Bay is the largest estuary in North America and is regarded as one of the most productive bodies of water on the continent. Its watershed contains six states: Maryland and Virginia, the two along its coasts, but also Pennsylvania, Delaware, New York and West Virginia.

Along with the District of Columbia, those states account for a population of nearly 18 million within the 64,000-square-mile watershed.

So what is the current issue in the Chesapeake Bay?

Water quality, according to DiPasquale.

Experts blame agriculture and urbanization for degrading the bay.

The growth of humans and waste are issues, but the use of fertilizer is a major pollutant, said Tom Horton, an author, former Baltimore Sun journalist and professor of practice in environmental studies at Salisbury University. He has lived in the watershed and covered the bay for years.

The contamination creates so-called dead zones in the water where there is low oxygen — something scientists call eutrophication.

Eutrophication occurs when light can’t reach the bottom of the bay due to pollutants in the water. Thus bottom-dwelling plants are unable to produce oxygen. A lack of oxygen in the water negatively impacts every living thing in the bay, as all require oxygen to survive.

Fithian, the Rock Hall town manager, puts much of the blame on Maryland’s neighbors to the north.

“We have made monumental steps in Maryland, but Pennsylvania and New York haven’t followed suit, which I can understand,” Fithian said.

The Susquehanna River, which flows through Central Pennsylvania, provides nearly half of the daily freshwater to the bay, and the river is fed by tributaries across the state. So water from rainfall might collect nutrients from fertilizer on a lawn and gasoline from a driveway before flowing into a waterway.

Then there is the biggest culprit: agricultural runoff — and it all ends up in the Chesapeake Bay.

According to U.S. Census reports, there were 59,309 farms in Pennsylvania in 2012.

While Pennsylvania might not be directly harmed by its own pollution in a massive way, it is having a detrimental effect on the water to the south.

“We are making progress, but there is still a lot to be done. We have no shoreline of the bay proper, but we try to talk about the watershed as a whole,” said Marel King, the Pennsylvania director of the Chesapeake Bay Commission, a group that advises the legislatures of Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia on issues important to the watershed.

When it comes to agriculture, “the rules have been in place, but there hasn’t been any robust enforcement or compliance. At the same time, we need to make sure resources are available to aid in compliance, because they can be expensive,” King said.

Buffer zones and cover crops are the simplest means to help alleviate pollution by nutrients, he said, by providing a physical barrier against runoff entering local creeks and streams. However, funding for those is tight in Pennsylvania.

“In Pennsylvania, we rely very heavily on federal support,” King continued. “Maryland and Virginia both have very large, state-dedicated funds for this purpose.”

King joked that while Virginia’s efforts are funded by a state budget surplus, in Pennsylvania, lawmakers often have trouble even passing a state budget.

In addition, “Pennsylvania is agriculturally dominated, so a lot of our work is going to focus on agriculture, but we need to work with that community. We do need something more,” King said.

Teachers on an educational field trip on Chesapeake Bay ~ photo by Bill Portlock/CBF Staff

Trees are the most cost-effective way to affect runoff, said Lane Whigman, the Pennsylvania outreach and advocacy manager of the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, another of what author Horton said are “hundreds” of groups dedicated to the bay’s health.

“In PA, as we look for solutions, our focus is on tress,” Whigham said. “They filter the water, provide us with clean air and there are so many great benefits of trees.”

The federal Environmental Protection Agency has long figured prominently in working on ways to help the Chesapeake.

“If we didn’t have the EPA, we wouldn’t have made the progress we have,” Horton said.

There has been much consternation in Washington about the Trump administration and the director of the EPA, Scott Pruitt, and what the new president’s attitude is toward the environment. DiPasquale said the bigger focus is on what Congress will be doing with the EPA’s budget, and, in particular, the portion allotted to the Chesapeake Bay.

The Chesapeake Bay Program has an annual budget of $73 million, but the House of Representatives currently has the budget set for $60 million.

That $13 million cutback would set back progress, DiPasquale said, as nearly two-thirds of the budget goes to the states in the watershed.

FallFest in Rock Hall, Maryland. Fishing and crabbing were once thriving businesses in this small bay town, but no more. ~ photo by Steven G. Atkinson

***

The Conowingo Dam is located near the Pennsylvania-Maryland border, 13 miles north of Havre de Grace, Maryland, where the mouth of the Susquehanna River opens into the Chesapeake Bay.

Built in the 1920s and opened in 1928, it was meant to help filter some of the pollution flowing from up north before it entered the bay proper. It does this by using a 14-mile reservoir where sediment is deposited.

Big storms have had a detrimental effect, however.

In 1972, Hurricane Agnes brought silt from above into the Chesapeake when its gates were opened, Ashley said.

Then came Tropical Storm Lee in 2011. Fithian said Maryland was affected in a relatively small manner by the storm itself, but Pennsylvania and New York were hit hard. To alleviate the risk of flooding to the north, about 40 of the dam’s gates were opened, depositing what experts approximate was 19 million tons of sediment into the bay, Fithian said.

With that much sediment now coating the bottom of the bay, there were bound to be impacts.

Clams and oysters can’t leave when pollution comes, Fithian said. While crabs and fish have the ability to swim away from a certain amount of pollution, shellfish don’t move themselves once they mature.

“It was the beginning of the end,” Fithian said.

Horton said Pennsylvania is behind in cleaning up the water draining south, adding to the pollution in the bay.

“Pennsylvania hasn’t done nearly enough,” he said.

There needs to be a better job done of communicating the science to the public across the watershed, Horton said, noting that there is a fiercer attachment to protecting the bay if people have grown up and lived closer to it.

Nesspor said when people come to visit Rock Hall, they are usually curious about the lives of the watermen and ask lots of questions about the bay and the crabs or clams.

“I try to educate them on the bay and raise awareness,” Nesspor said. “It’s about the health of the bay.”

****

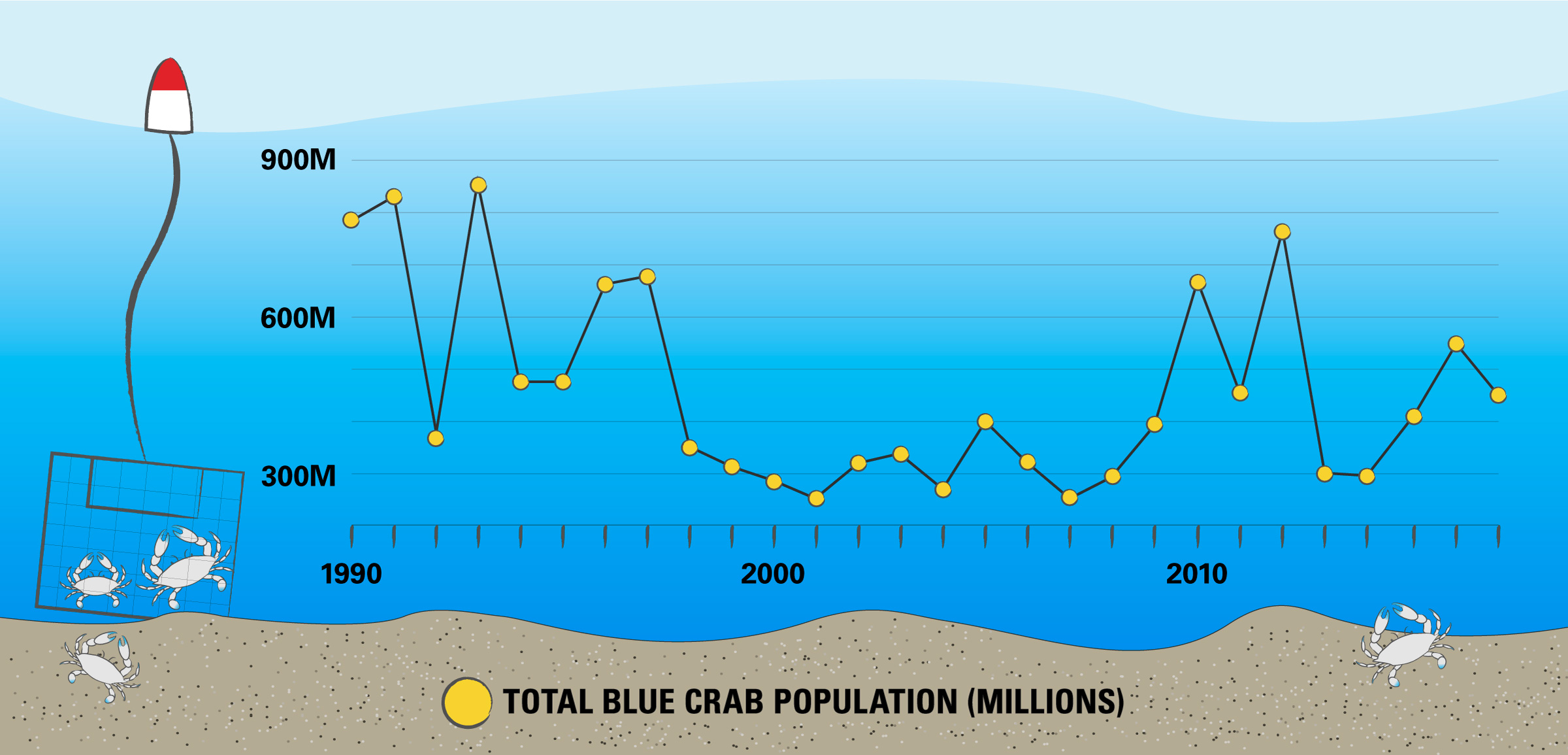

How healthy is the bay in terms of its annual harvest of seafood?

Each year between 1997 and 2015, the harvest of blue crabs, commercially, ranged from nearly 23 million pounds to more than 66 million pounds, according to Maryland state records. In 2015, the last year in which statistics were available, commercial crabbers brought in nearly 29 million pounds.

Commercial oyster production has also varied. In 1998, there were nearly 2.5 million pounds harvested, but in 2004, there were just under 43,000 pounds. The 2015 figures show 1.2 million oysters harvested.

Fish harvesting has also varied year to year.

DiPasquale said pollution, fishing, disease, water temperatures and weather all play roles in the year-to-year harvest fluctuations.

“We are constantly changing this ecosystem, trying to see what impact these effects have and adjust from there,” DiPasquale said.

***

Horton said there are some signs of progress, including uptrends in oxygen and light, combating nitrogen and phosphorus. This means dead zones aren’t lasting as long and it seems to be an honest trend.

“In the Chesapeake region, we have a strong focus on delivering clean water, not only for nature, but for people too,” said Mark Bryer, director of The Nature Conservancy’s Chesapeake Bay Program.

Oysters are part of the solution, because they are so-called filter feeders and can “clean” nearly 50 gallons of water a day.

In the 1940s, there was a massive harvesting of oysters for shells used in construction — mountains of shells were taken out at an unsustainable amount, Bryer said. At the same time, pollution was coming into the watershed, making the water quality worse.

Then, in the ‘80s and ‘90s, he said, there were disease outbreaks, with oysters dying at alarming rates. For a couple of decades, restoration efforts were minimal.

Scientists established oyster sanctuaries – areas that were off-limits to harvesting. Those areas are growing.

Now, Bryer said, the largest oyster restoration has been completed in Harris Creek on the Eastern Shore just south of Kent Island with a 350-acre reef – “it’s really massive, really cool project.”

“Things are turning around, but [they] can’t turn around entirely in a decade,” Bryer said.

The success of Harris Creek is being replicated elsewhere in Maryland and in Virginia, Bryer said, and it shows that when people work together, they can accomplish something. Oyster populations have double or tripled in each of the last five or six years.

But that sense of accomplishment isn’t always shared by those whose livelihoods depend on those same oysters, because they are not permitted to harvest them.

Bryer said the reefs were created to purify water, restore the habitat and fight erosion, and there are no plans to open up the sanctuaries to harvesting.

A similar sanctuary was placed in the Chester River.

“They just took it away from commercial oysters,” Fithian said.

Nesspor said claims that watermen have overharvested oysters over the years is not true.

“It’s easiest to pick on and blame it on us because we don’t have the numbers,” Nesspor said, adding that watermen are the best conservationists, because they do not want to put themselves out of business.

****

Bay experts are generally cautiously optimistic about the Chesapeake’s future.

Waterman's Day on the bay ~ photo by Steven G. Atkinson

DiPasquale said the goal should be to “restore balance” and make the bay sustainable.

“We are always going to be responding,” he said.

Bryer said the challenge is to reduce the agricultural pollution in ways that work well for farmers.

“We have done a lot of the easy stuff,” he said.

Horton said while some progress has been made, it’s too early to determine if the “grand experiment” of restoring the Chesapeake Bay by 2025 will work.

“We’ve taken this world class resource and on a world class scale screwed it up,” Horton said. “And now we are trying to put it back together.”

~ 12.07.17