Joe Paterno's statue at Penn State on the day he died, Jan. 22, 2012. Six months later the university would remove the statue. ~ Photo by John Beale

Along the east side of Beaver Stadium, the 107,000-seat home of the Penn State Nittany Lions, a few fans take time out from tailgating nearby on a rainy October day to place clumps of blue and white carnations between two young linden trees.

The flowers and trees mark where the statue of Joe Paterno once stood. The coach’s image was removed four years ago after the Jerry Sandusky child-sex-abuse scandal that captivated an entire country. Though it appears as if the statue never existed there, diehard fans still honor Paterno with tributes in the university colors.

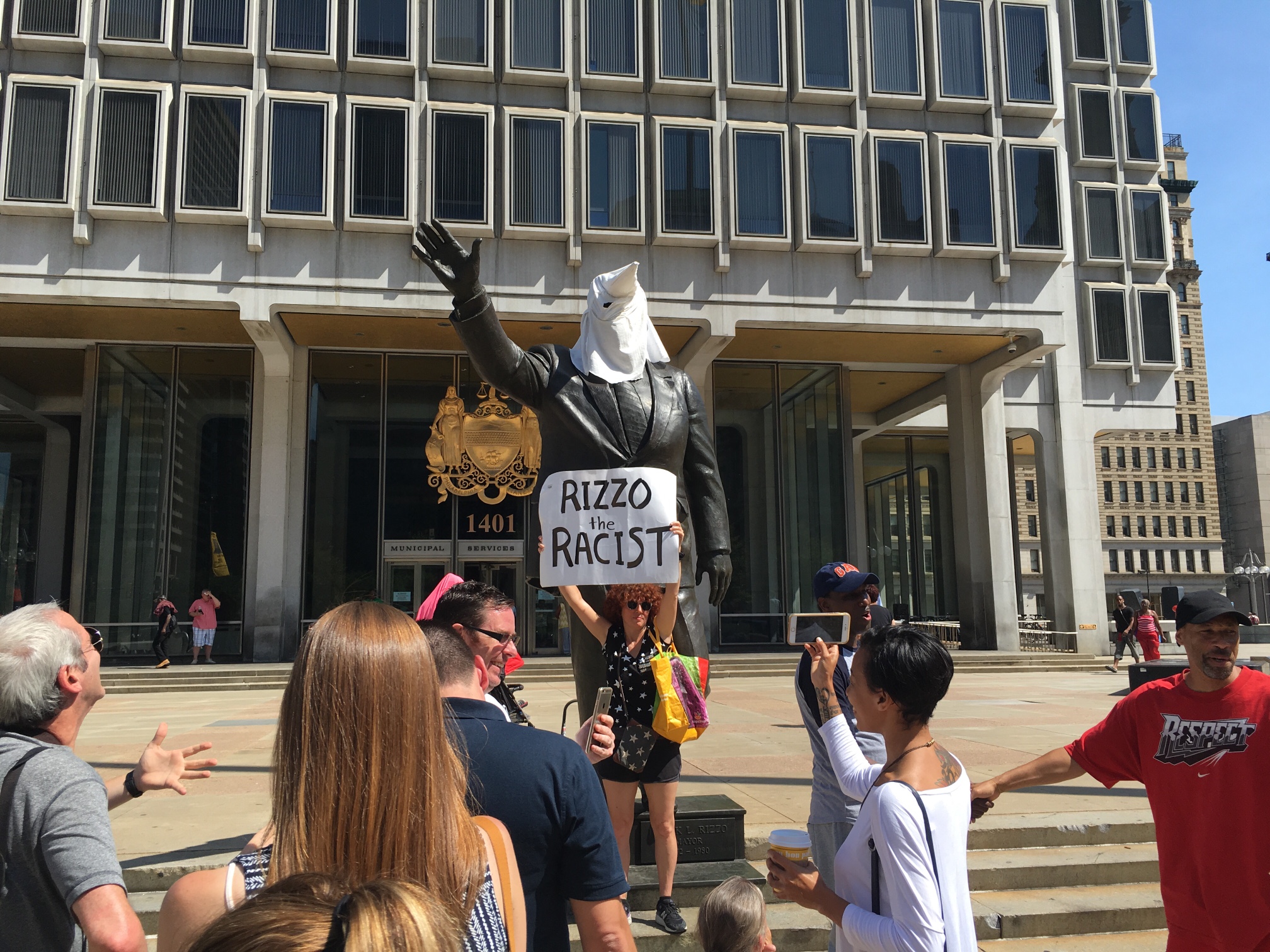

Two months before that football Saturday, 190 miles east of State College, 34-year-old Asa Khalif draped a Ku Klux Klan hood over a 10-foot-tall statue of Frank Rizzo, Philadelphia’s former police commissioner, mayor and larger-than-life figure. The statue stands prominently in front of the Municipal Services Building across from City Hall. “We are not going to celebrate racist bigots,” Khalif, a member of the Black Lives Matter movement, said in a September interview.

Two protesters placed a KKK hood on the Frank Rizzo statue of the former Philadelphia police commissioner and mayor.~ Photo by Shannon Wink/Billy Penn

And just nine weeks later, 150 miles southwest of the Rizzo statue, the Historic Preservation Commission of Frederick, Maryland, made a decision: The bust of Roger B. Taney (pronounced TAW-knee), former chief justice of the United States, the man most responsible for the 1857 Dred Scott decision that denied citizenship to African Americans, will be removed from the honored place it has occupied for 85 years in the City Hall courtyard.

These three unrelated incidents are prime examples of what has become an increasingly popular form of social protest across the United States, one that highlights the clash between history and cultural sensitivities.

Dozens of statues and memorials that have stood for decades are coming under attack from critics who say it is time to stop honoring people who once were venerated but now are controversial. These include Confederate heroes such as General Robert E. Lee and President Jefferson Davis. They include Bill Cosby, the television star, whose statue at Disney World was removed last July after unsealed court documents from 2005 showed that Cosby admitted drugging women in order to have sex with them. And they include Thomas Jefferson, the author of the Declaration of Independence, whose statue at the University of Missouri some students are petitioning for removal because he was a slave owner and possibly a rapist.

“Where I’m not as happy is that you can’t obliterate history.” William Blair, history professor at Penn State

***

It may be bold for Frudakis to take on the project of a Paterno statue when his Rizzo statue is under heavy scrutiny.

Frudakis sculpted the statue of Rizzo, the former Philadelphia police officer-turned-mayor, seven years after Rizzo’s death in 1991. It was commissioned and paid for by Rizzo’s family. The fact that it stands on public property outrages some members of the Black Lives Matter of Pennsylvania chapter.

“I think it’s a slap in the face to black and brown people, who have been brutalized by the legacy that they want to honor,” said Khalif, who made headlines this summer when he placed the Klu Klux Klan hood over the statue. Police removed the hood soon after.

As mayor from 1972 to 1980, Rizzo was credited with lowering the city’s crime rate, and he was running for another term when he died. But it was Rizzo’s relationship with some African Americans and other minorities that has led to the controversy over the statue.

As police commissioner in 1970, Rizzo blamed the shooting of one of his police officers on members of the Black Panther Party, arresting 14 of them and having them stripped naked in the middle of the street. Pictures of the incident made front pages everywhere. A few days later, all charges against the Panther members were dropped.

Rizzo’s obituary in The Philadelphia Inquirer said he sometimes referred to blacks as “n—–s” in private conversations.

Khalif said he just wants the Rizzo statue removed from public property where hundreds walk past it every day. “If they want to preserve it and worship it,” he said, “then they can move it to a private place and light their candles and kneel before it, but it should not be on public property whatsoever.”

There is nothing new about protesting Rizzo, Khalif said. Previous generations have done the same. “It’s our duty to pick up the mantle and carry that onto completion that our parents have started,” he said. “I remember my grandparents talking about Rizzo when he was a big cop. And I remember my parents talking about their experiences with Rizzo when he became mayor and again allowed racist Philadelphia police officers to have a hand in profiling and brutality of black and brown people.”

Savage said it was common for statues to be erected by people who did not consider how minorities felt about them.

“When a monument was erected, not every group had played an equal role in the conversation that led to that monument. Some groups were totally excluded,” Savage said. African Americans “didn’t have power at all” when Rizzo was mayor. “Now it is part of their attempt to make their voice heard in public and to say, ‘Hey, these guys like Rizzo don’t belong here. We don’t honor these men anymore. We never did.’ ”

Brian Curran, a professor of art history at Penn State, noted the role social media has played in the effort to take down statues and memorials – from organizing demonstrations to luring media coverage.

“There’s a networking of things like Facebook, Twitter and all of that, so it’s much easier to whoop up support for something,” Curran said. “It’s much easier to generate a petition, get publicity that way.”

Opponents of the Rizzo statue collected almost 1,500 signatures online.

In August, after Khalif’s protest, Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney issued a statement to reporters: “The late Mayor Rizzo means something, both good and bad, to many more Philadelphians than that. I am happy to have a dialogue about the future of Rizzo’s likeness in relation to its location, but that dialogue won’t be started and finished over a few days and a few hundred signatures.”

Frudakis, who sculpted the Rizzo statue, is watching the case closely. He said he favors taking down statues to people he called “actual monsters,” but he said the answer to solving the issue of controversial statues might be more, not fewer, statues.

Perhaps a sculpture of an African American could go across from that of Rizzo, Frudakis said. He noted, however, that pieces of art do not come cheap; a statue can cost upward of $100,000. “But if people feel strongly enough about the situation, they should raise the money,” he said.

Removing a statue can cost around the same amount of money, or even more.

A commission deciding the fate of statues of Confederate generals Robert E. Lee and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson in Charlottesville, Virginia, could face an estimated $700,000 bill to remove the pieces.

Savage suggested that a cheaper option could be plaques placed near the statues. That way, he said, people could learn the good and the bad about those honored by the statues – and then they could make their own interpretations.

***

The city of Frederick, Maryland, has already put Savage’s advice into action.

In 2009, a plaque explaining the background of the Dred Scott decision was placed next to the statue of Taney. In part, the plaque said Taney’s language in the opinion was “subject to immediate criticism and enraged abolitionists.” It also said the decision was “one of the events that led the United States into a civil war.”

But even with the plaque, protesters urged for the sculpture to be removed.

Taney, a supporter of slavery, was on the Supreme Court of the United States from 1836 to 1864. He was chief justice when the court ruled in the Scott case in 1857 that blacks, free or enslaved, were not citizens of the United States and thus could not sue under the law.

The decision was overturned in 1868 with the enactment of the 14th Amendment, which grants citizenship to anyone born or naturalized in the U.S.

~ Photo by Sam Yu

Donna Kuzemchak, who is in her fourth term on the Frederick Board of Aldermen, said she has fought for the removal of the statue since 1999, her second year in office. She said voters have told her they didn’t want Taney’s statue in front of City Hall.

The Historic Preservation Comission’s Oct. 13 decision to remove the statue also included the removal of the accompanying Dred Scott plaque as well as a bust of Maryland’s first governor, Thomas Johnson, a slave owner. “Everyone agreed that it was an inappropriate place to have that statue,” Kuzemchak said.

Kuzemchak said the busts may be placed in a local cemetery where some of Taney’s family are buried. Johnson is also buried there.

Kuzemchak said that although Taney was a respected public official, having served as the U.S. attorney general and secretary of the treasury, “we will forever be known by the worst thing we’ve ever done.” She was careful to note that six other justices also ruled against Dred Scott, so all of the blame shouldn’t be placed on Taney.

Kuzemchak added that a line needs to be drawn when it comes to keeping certain statues for the sake of using them to interpret history.

“Do you think they should have a monument or statue of Hitler in the middle of Germany?” she asked.

***

Even as statues are coming down or their fates are being debated, historical preservation groups and others are fighting to keep some just where they are. And others are looking at ways to avoid controversies in the future.

“We believe historic places, including Confederate memorials, can be catalysts for a necessary and worthwhile civic discussion,” Germonique Ulmer, vice president of public affairs for the private, nonprofit National Trust for Historic Preservation, said in an email.

In some states, such as North Carolina and Tennessee, lawmakers are considering legislation that would make it more difficult to remove statues. In the South, where statues of Civil War leaders stand tall, the debate has been particularly contentious.

While states and local governments have their own laws and rules pertaining to statues, the federal government has a straightforward vetting process.

The federal Commemorative Works Act, enacted in 1986, lays down requirements before a statue or memorial can be erected on federal property in Washington, D.C. A person must be dead for at least 25 years before a statue can be put up in his or her honor. And 10 years must pass after the conclusion of a war before military works can be commemorated.

The theory is that the passage of time allows reflection to determine whether a person or event should be celebrated.

The National Capital Planning Commission, which considers statues and memorials on federal property around the nation’s capital, works closely with Congress in determining what statues should be erected. The commission teamed with the National Park Service and Van Alen Institute, a nonprofit design organization that focuses on public spaces, to start a competition called “Memorials for the Future.”

One of the partnership’s key findings: “As time passes, new information is exposed and cultural values shift, sometimes creating disconnects between a memorial’s original message and representation and modern-day perceptions.”

Many of the submissions focused on memorials dealing with immigration, climate change and technology, not specific people or events that might become subjects of controversy.

Savage, the Pitt professor and author who has delved into the issue of controversial statues, said the nonspecific ways to memorialize people or events may be what is to come. “That’s something we’re going to hear more about,” Savage said. “I think the era of the static monument may start to come to an end.”

Blair, the Penn State history professor, said he is concerned about “obliterating history.” He suggested that states and local governments should look at the model of Richmond, Virginia, which recognizes the harshness of a past that included slavery.

The Slavery Reconciliation Statue, erected in 2007, is part of the Richmond Slave Trail that is designed to raise awareness of the area’s history. The city has also placed a Civil Rights Memorial next to a statue of Confederate Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson.

“You don’t want to forget that past,” Blair said, banging his hand on a table for emphasis. “If you forget it, you’ve taken away a huge part of American history that says, ‘Everything we did wasn’t always cool.’ ”

~ published 10.25.2016 ~