An invasive fly from Southeast Asia landed in eastern Pennsylvania five years ago and is spreading west.

Always keep your windows up. Check grills, tents, tables, yard games. Don’t park under trees in the quarantine zone. Check yourself before getting in the car.

If this sounds like the start to a plague-ridden dystopian novel, it’s not. It’s the invasion of the Spotted Lanternfly.

These inch-long flying bugs, which resemble moths but with bright, red-spotted wings, are everywhere, at least in much of eastern Pennsylvania. They arrived here from Southeast Asia five years ago, and since landing in Berks County, about 65 miles northwest of Philadelphia, they’ve spread to at least 14 of the state’s 67 counties, all of which are now part of a quarantine zone. (More about that later.)

Lanternflies – full scientific name Lycorma delicatula – attach themselves to trees, to vehicles and to people. Their eggs look like mud splatters, and the tiny critters seem to be as big a topic of conversation in the affected areas as the impeachment controversy surrounding President Trump or whether Bryce Harper joining the Phillies was worth $330 million.

How prevalent are spotted lanternflies? Consider:

- There are Facebook groups about the insect, one claiming as many as 1,100 members and averaging 10 posts a day.

- They have been a boon to lawn and landscape services and pest control companies, such as the “Spotted Lanternfly Killers.”

- Penn State University has created a hotline to report sightings and answer questions: 1-888-4-BADFLY.

- These icky little creatures have inspired a public service announcement horror film, a song called “Die, Die, Die Spotted Lanternfly” and a woman who makes necklaces from their wings.

- On Zazzle, an online shopping site, you can buy a dozen personalized Spotted Lanternfly party hats for $22.20. On another site, ByShirts, you can get a T-shirt that says “Spotted Lanternfly Ninja.”

- There’s even a lanternfly app called Squishr for people who want to record how many lanternflies they kill. It was developed by a suburban Philadelphia man and his family and has gotten more than 3,200 downloads in four weeks.

- The state Department of Agriculture has created “The Spotted Lanternfly Fun Activity Book” that lets children color the bugs, spot their egg masses and do a spotted lanternfly word search (featuring words like “nymph,” “bug” and “invasive.”)

- In February 2018, the U.S Department of Agriculture announced $17.5 million in emergency funding to combat the lanternfly in Pennsylvania, and the bug has also spread to New York, Delaware, New Jersey and Virginia.

This is but a sampling of all-things lanternfly that have appeared throughout the media, online and otherwise.

For Elise Schaffer, the project assistant on Penn State Lehigh Valley’s Arts Initiative project, the bugs particularly became a nuisance last year, when she had an internship in downtown Allentown.

The lot where she parked was so lanternfly-heavy that getting in and out of her car without getting lanternflies in it was “impossible,” she said.

Schaffer said the weirdest moment came when she and her colleagues went to Coca-Cola Park, home of the minor league baseball Lehigh Valley IronPigs, to collect lanternflies for an art project.

They went armed with a Shop-vac to collect the bugs.

“Their whole staff was there setting up for the baseball game, and they’re watching us suck up bugs with a vacuum cleaner,” Schaffer said. “It was really funny.”

What is not so funny is the damage lanternflies can cause.

Simply put, the spotted lanternfly sucks the life out of plants. Literally.

To show how the lanternfly eats, Karen Kackley-Dutt, a Penn State Lehigh Valley biology professor studying the lanternfly, tells people to imagine that they’re going to tap a maple tree for syrup using a spiked, metal spout called a spile.

“You bang it into the tree until you’d get into the sugar conducting tissue of the tree, which is called the phloem…where the sugar is conducted in plants,” Kackley-Dutt said.

“They just sit there like they have a straw, sucking in the plant sap,” she added.

Unlike the production of syrup, however, the lanternfly is only sucking out the tree’s lifeblood to feed itself.

After the lanternflies feed, the sugar and sap they’ve eaten are then concentrated into a substance called “honeydew” and excreted.

“They almost, like, shoot it out,” Kackley-Dutt said. “Like, if you’re near these guys, it looks almost like rain, this honeydew that they’re excreting.”

The sticky excretion is one of the problems. Fungi called sooty mold — because it looks like black soot — can grow in the honeydew, Kackley-Dutt said. “And then what happens is that black sooty mold covers over the leaf surface or anything it’s on — a car, a picnic bench, a sidewalk, any of that kind of stuff….”

Heather Leach, who is the Penn State spotted lanternfly extension associate, said researchers are trying to figure out more of what the bugs eat, but so far the main theme they are seeing is that lanternflies really like vigorous plant species.

“They like things that are really strong growers, so grapes are one of those, but we also see maples and black walnuts, willow trees,” she said. “[T]hey feed on practically anything, and it’s dependent on what’s in the landscape.”

Leach said lanternflies are really impacting vineyards.

“[W]e’re seeing really significant crop loss and extremely high levels of spotted lanternflies feeding on vines, and then we’re also seeing damage to some of our tree species here, especially things like maples, oaks, willows, poplars,” she said. “Things that are often planted in people’s backyards or street trees.”

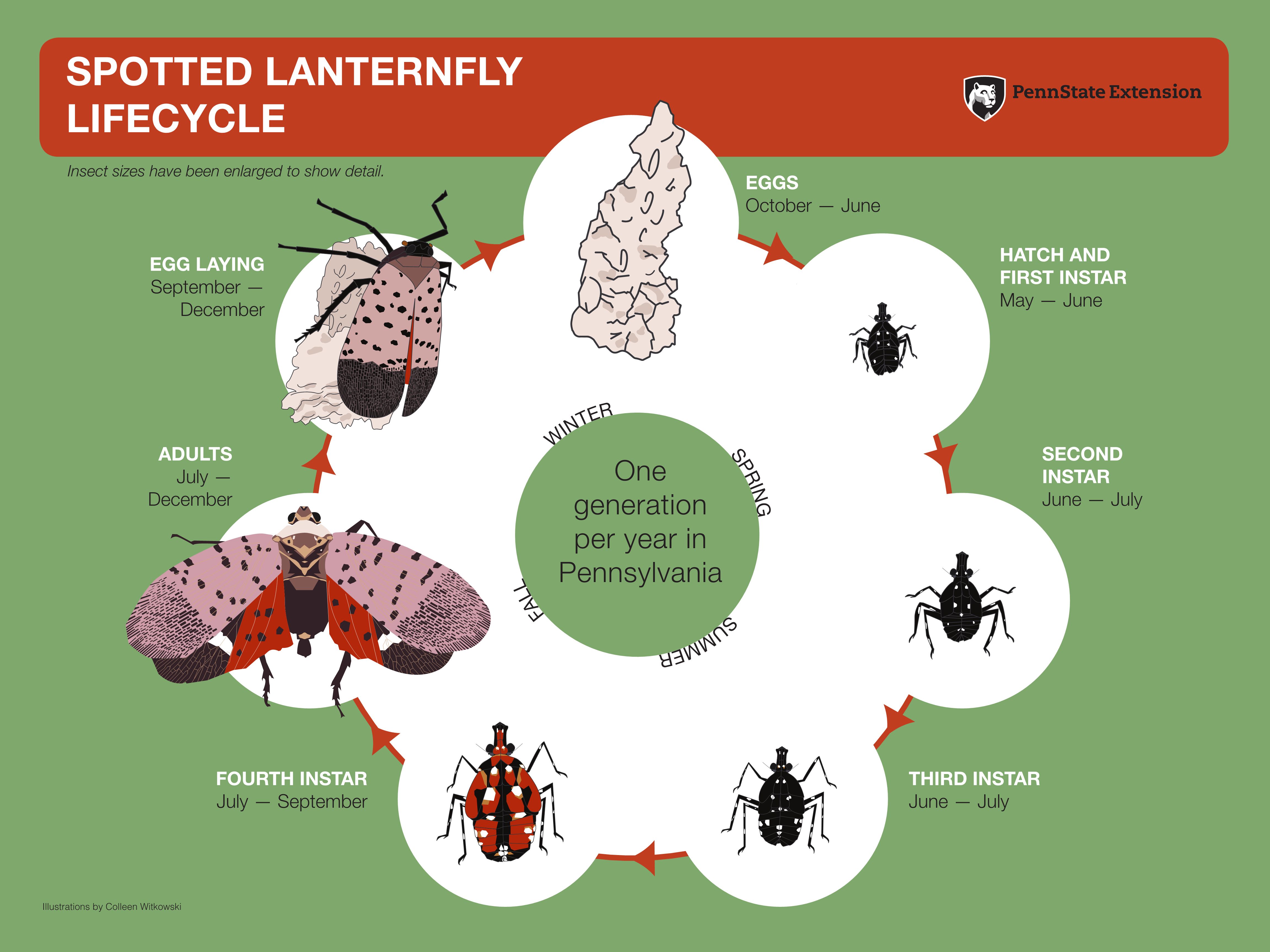

Kackley-Dutt said lanternflies attack trees from the time they hatch from eggs until the time they die as adults.

“They can feed on small twigs, but they don’t feed on the leaves and they don’t feed on the fruit,” Kackley-Dutt said. “They’re only feeding on the stems of the plant.”

The Tree of Heaven, native to Asia, is one of the lanternfly’s foods. It’s an invasive plant species that came to Pennsylvania before the lanternfly, which provided the bugs a feeding ground.

“They got here, and it’s like,’ Oh, here’s our normal tree. And then here’s a bunch of other ones, too,’” Kackley-Dutt said.

A problem in the U.S., Kackley-Dutt said, is that whereas lanternflies would have predators and competition from other insects in their natural environment, here they have nothing to keep them under control.

“They come here and it’s like a smorgasbord. There’s nothing to stop them, nothing that’s eating them, killing them, and they have everything to choose from, she said. That’s the way with many invasives — they don’t have to obey the natural controls that our native insects and plants do.”

Kackley-Dutt said that the long-term impact of lanternfly feeding on plants like sugar maples or walnuts isn’t known yet, although it’s already having an effect.

Pennsylvania is the number one producer of hardwood lumber, she said, and it’s preventing lumber manufacturers from being able to ship wood because of the quarantine.

Jeff Easterling, president of the Northeastern Lumber Manufacturers Association, said hardwood manufacturers cannot harvest trees or transport lumber from the quarantine zone “for fear of moving the pests or egg masses.”

“So it will definitely impact the hardwood lumber industry that would harvest anything of that nature,” Easterling said.

A lanternfly nymph. ~ photo by Emelie Swackhamer

Part of all the awareness campaigns – the blogs, the apps, the art projects – is to inform people about the lanternfly and the problems it causes.

Elizabeth Blose, a teacher in the Parkland School District in Allentown, turned the lanternfly infestation into a teaching opportunity, starting a “Spotted Lanternfly Prevention” blog for her classroom.

“As educators, I think we’re always trying to find experiences for the kids that are going to be engaging but also authentic, so create a learning environment that the kids care about,” Blose said.

At Penn State’s Lehigh Valley campus, Ann Lalik, gallery director and arts coordinator, said students and faculty participated in a contest to see who could collect the most lanternflies.

“It was just a 20-minute competition, but we collected about two pounds of bugs, which is kind of a lot because they’re tiny,” Lalik said.

Brad Line, who along with his two young sons developed the app Squishr, said he did not expect to reach so many downloads so quickly.

He said that the initial Android version was “a little buggy,” but it was re-released with fixes. While he said he never thought about invasive species before creating the app, people now tell him he should create apps for stinkbugs and invasive fish.

There is a way to tell if a bug you see is a spotted lanternfly. Leach recommends people poke their fingers toward it, because “they’re very strong jumpers,” not like stinkbugs or moths, which fly or walk away.

Pennsylvania officials established the quarantine zone to let people know where the spotted lanternflies have been found. If people are traveling from those 14 counties to unaffected areas, they are supposed to inspect their vehicles so they don’t accidentally spread the bugs.

Researchers are investigating ways to suppress the lanternfly, from classic biological controls to other methods. A particular kind of wasp, one of the lanternfly’s predators, has been imported from China. But those wasps are in their own quarantine zone to make sure they won’t introduce anything harmful to the environment.

Scientists are also studying fungal pathogens as a means to control the lanternflies.

David Jackson, an extension educator in renewable natural resources, said the spotted lanternfly doesn’t need the Tree of Heaven to survive. He said the Tree of Heaven can be used for what he calls a “trap tree.”

“So that’s kind of a really neat thing about Tree of Heaven is that we can use it to selectively control spotted lanternfly populations through an insecticide treatment,” he said.

Leach said getting rid of the lanternfly population will not be easy.

“We’re dealing with a pest that’s present throughout the area. It feeds on so much, there aren’t good controls for it beyond broad-spectrum insecticides, which we don’t want to broadcast spray everywhere,” she said. “And so what that basically means is that eradication isn’t likely. It’s a pest that we’re at millions, if not billions, in the population.”

She does believe that there’s hope.

“I do think, though, that we can continue to take steps that will hopefully reduce the population and contain it as much as possible,” she said, “so that we can slow down the spread before it gets to new areas and causes more damage.”

~ 10/25/2019

.