Public schools and private schools struggle with fair competition in Pennsylvania

STATE COLLEGE, Pa. _ Stop us if this is a surprise, but Pennsylvania is a big high school sports state.

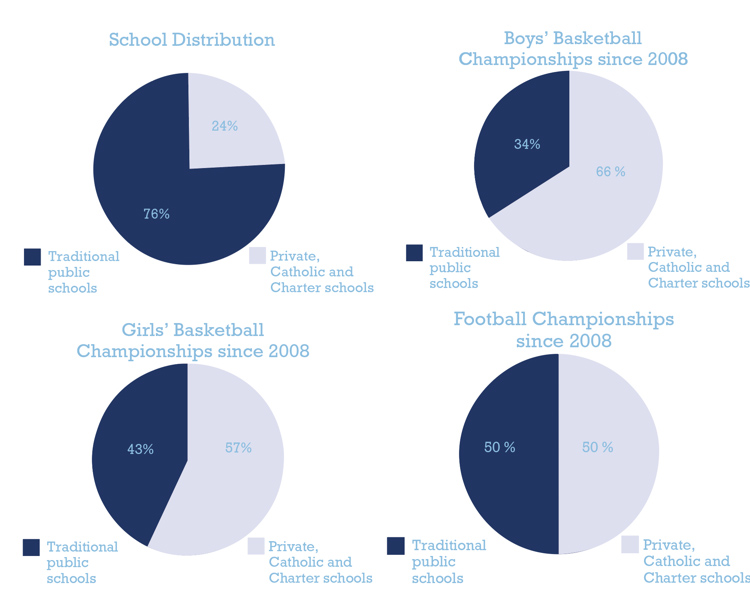

How big? Every year, more than 350,000 teens compete in organized high school sports across six divisions, according to the Pennsylvania Interscholastic Athletic Association’s website. Three-quarters of those students attend traditional public schools. The rest go to private, Roman Catholic and charter schools, based on a count of PIAA figures.

But, while these private schools are fewer in number, when it comes to hoisting championship trophies at the end of the year, they often have an edge.

Cathedral Prep won their 4A semifinal playoff game, defeating Bishop McDevitt 48-7. ~ photo by Giana Han

Take, for example, the 3A division in boys basketball, which once had schools with as many as 411 male students, and now _ under a revised classification system that went into effect in 2016 _ can have as few as 149 males students.

Over the past decade, public schools have not won a single 3A boys basketball title.

Eight of those championships went to one school, Neumann-Goretti, a Philadelphia-based Catholic school.

“We compete at whatever level,” said Carl Arrigale, the Neumann-Goretti coach. “We’ve had a solid program for a long time, and we build a culture. The guys that leave pass it on. The older guys pass it onto the younger guys. We’ve had a lot of stability.”

The Saints’ 74-17 record over the three years ending last March is just one example of how dominant private schools have been on the Pennsylvania sports scene. But now, the public schools have had enough.

They say it’s about more than just hard work and argue the state’s high school sports system is stacked against them. They are demanding reform, and even separation, from their private rivals.

By the numbers

In Pennsylvania, high school sports are governed by the PIAA. The state is divided into 12 geographic districts and, within each district, schools also are divided into classifications, determined by enrollment size.

For many years, there were four classifications, ranging from 1A to 4A, for football and girls and boys basketball, and three classifications for the rest of the sports.

During the 2016-2017 school year, however, two more classifications were added to football and girls and boys basketball, and one was added for other sports. The idea was to give more schools the opportunity to participate in state playoffs, a move aimed partly staunching complaints about private school dominance.

It hasn’t worked out perfectly. For example, now there are gripes about watered down competition because there are fewer schools in each group.

It also hasn’t affected which schools are dominating.

For example, Archbishop Wood, near Philadelphia, won three 3A football titles before the move to six classifications. After the change, it moved to 5A, but it continued to find success and won the next two championships.

Across football and basketball, there are five other schools with similar stories. The championship imbalance has been a theme for years.

And across every classification, in the 10 years ending last spring, private, Catholic and charter schools were particularly successful in the most high profile sports, winning 66 percent of the boys basketball titles as well as 57 percent of girls basketball titles and 50 percent of football titles.

Meanwhile, when the other team sports are thrown in, the private school share of titles drops down to about 33 percent, according to the PIAA District 3 website.

“So, 50-50,” said Mike Bariski, the athletic director and boys’ basketball coach at Pittsburgh’s Lincoln Park Performing Arts Charter School, summing up what he sees as the end result. “I know there’s a lot more traditional schools — but 50-50, I don’t how much more fair you can get than that.”

Not everyone sees the split between the traditional public schools and the others as equal.

“Less than 20 percent of the membership is claiming between 60 percent and 2/3 of the titles,” said Len Rich, the Laurel School District superintendent and a Western Pennsylvania Interscholastic Athletic League board member. “So obviously there’s a degree of inequity based upon classification, then you need to do root cause analysis and see exactly what that is.”

“Less than 20 percent of the membership is claiming between 60 percent and 2/3 of the titles,” “So obviously there’s a degree of inequity based upon classification, then you need to do root cause analysis and see exactly what that is.” Len Rich, the Laurel School District superintendent

The private school edge

What explains the difference between private and public schools?

Public school administrators point to the way Catholic and charter schools get their students.

Public schools enroll students from their school district, which is defined by geography. Every student in a given district goes to that school unless they decide to be homeschooled or go to a private, Catholic or charter school.

Private, Catholic and charter schools, by their nature, must recruit students. They have no hard and fast geographic boundary. Instead, they must reach into various communities, and multiple school districts, to draw students.

And when top recruits start pouring into one private school in a city — for example, Roman Catholic in Philadelphia, which has won three of the last four top division boys’ basketball titles — the differences start to be seen as inequality.

“It’s important that wins come on equal grounds, that you’re playing against opponents that have the same set of rules you have,” said Mike Williams, Manheim Central’s former head football coach.

Williams has 34 years of coaching experience and a state championship under his belt. Those years have led him to conclude public school sports programs are undervalued, and they’re “taxpayers’ biggest bargain.” He’s also had time to reflect on the relationship between private and public schools.

“When a team can gain an advantage from a different set of rules, and they win all the time, then that becomes a rallying cry for people to kind of change the look,” Williams said.

What’s the problem?

The WPIAL, also known as District 7, has been the driving force behind playoff reform.

Although the District 7 public and private schools are fighting for different solutions, there seems to be a consensus on what the problem is.

Bariski, the athletic director for Lincoln Park, cited the way athletic transfer requests are reviewed as the main issue in high school sports.

“Right now, with 12 districts, you basically have 12 judges and 12 juries,” Bariski said. “And they can look at (transfers) all differently. And a lot of times what happens is districts look out for their own well-being rather than the state’s.”

The WPIAL leads the state in transfers requested but also transfers denied, said Rich, the Laurel School District superintendent, but other areas of Pennsylvania are not so strict.

Penn State basketball’s Lamar Stevens transferred from Haverford High School, a public school outside Philadelphia, to the basketball powerhouse Roman Catholic.

He said he wanted to play at a higher level of competition, which could be found in the Catholic league, but he found himself sacrificing the level of education, which he felt was higher at his public school.

Stevens is not sure he made the right decision in transferring, and he sees the pros and cons of the move. But he learned something through the experience that he would share with younger athletes.

“If you’re a high level player, they’re going to find you no matter where you are,” Stevens said. “You don’t have to be at a big time basketball school to get the recognition or to play in front of huge crowds.”

People in other districts are focused on other issues.

In eastern Pennsylvania’s District 3, Aaron Menapace, the Hamburg High School athletic director, is more interested in the classification system rather than transfers.

The enrollment number that Menapace reports to get put in a classification doesn’t tell the whole story.

About 20 percent of the kids at Hamburg take classes at a career and technology school and don’t have the option to participate in a sport, Menapace said.

Meanwhile, private schools aren’t sending students out to other schools. Rather, they’re taking students in, and those students are often outstanding athletes. The end result? Hamburg winds up overmatched.

“The problem for me is the demographic of our school and private schools is so drastically different that we end up being, I think, classified the same as them when we should not be,” Menapace said.

“If you’re a high-level player, they’re going to find you no matter where you are,” Stevens said. “You don’t have to be at a big-time basketball school to get the recognition or to play in front of huge crowds.” Penn State basketball player Lamar Stevens

Why now?

Pennsylvania private and public schools have been playing together since 1972, when Act 219 of 1972 was passed by the General Assembly.

“Private schools shall be admitted, if otherwise qualified, to be members of the Pennsylvania Interscholastic Athletic Association,” it states.

But things have changed a lot since 1972, and tension has been building.

Six years ago, the Archdiocese of Philadelphia, driven by dropping enrollment rates, came out with a statement that it was moving toward open enrollment. Students no longer had to attend their local Catholic school and could now attend from anywhere—and not just from anywhere within Pennsylvania.

“Regardless of where you live, you can drive by six Catholic schools to go to this one. There’s no longer a geographic boundary,” Menapace said. “And when that happened, some schools became wrestling schools, and some schools became football schools and some schools became basketball schools.”

A look around the nation

Cathedral Prep’s wide receiver Skyler Neely breaks a tackle in the 4A semifinal playoff game against Bishop McDevitt. Cathedral Prep won 48-7. ~ photo by Giana Han

Pennsylvania is not alone in its struggle.

Across the country, states are tweaking classification numbers, enrollment multipliers and competition formulas in an effort to give public school and private school athletes the same opportunities.

But, in neighboring Maryland, there is a notable lack of conflict. Public and private schools compete in separate playoffs and always have. They’re governed by different bodies, and joining has not been a topic either side has broached, at least not formally.

The Maryland Public Secondary Schools Athletic Association governs the public schools, but it allows non-member private schools to compete in regular season play if they sign an agreement to follow the same rules as the public schools.

There are several associations private schools can join. Those groups have different rules and standards of competition than the MPSSAA does.

MPSSAA assistant director Jason Bursick said he thinks one of the reasons there hasn’t been a problem is because the private schools are happy to follow their own rules rather than submit themselves to the MPSSAA’s rules.

Bursick is from Pittsburgh, so he’s familiar with the PIAA. He said he can see Maryland’s system working there, but he understands that Pennsylvania has legislation, Act 219, that complicates the situation, which Maryland does not have.

Other nearby states, such as New Jersey and Virginia, have systems similar to Maryland’s.

Put a Band-Aid on it

Generally, the PIAA does not move fast when enacting change, according to those pushing for the reform.

But this July, in an uncharacteristic move, the PIAA approved two new rules that take a step towards trying to even the playing field.

The first deals with transfers.

Previously, transfer requests were vetted with a presumption of eligibility. Now, transfer students in 10th grade or above must prove hardship or they sit out the postseason.

It’s become more punitive, Bariski said, especially for kids moving to private, Catholic or charter schools.

“Most of the transfers (to traditional public schools), if a kid moves, they moved,” Bariski said. “But when you go to a charter, private or Catholic school, you don’t move. You just change schools. And that becomes a challenge of eligibility for the student.”

The other new rule deals with both transfers and classifications, and has not been well received.

Referred to as the competition formula, the new rule, at its simplest, states that if a school hits benchmarks in terms of victories and transfers, it must move up a classification to presumably better competition.

In practice, the formula is a point system. State championship wins are worth four points, state semifinals are three, state quarterfinals are two and district or sub-regional championships are one.

If, after a period of two years, a school earns six or more points and has a certain number of transfers on the team, it moves up. The number is determined by the sport. Football is five transfers in two years, while basketball is two in two years.

The effects of this new rule won’t be visible for years, but many already have an opinion on it.

“The proposed success formula is anything but,” said Rich, the Laurel school district superintendent and a District 7 board member.

All it does, he said, is take the private school that’s causing problems in 1A and make it 2A’s problem.

Several administrators pointed to Kennedy Catholic from Hermitage, north of Pittsburgh.

It has won the past three championships in the smallest division, and it went 21-4 last season, led by the No. 1 and No. 10 basketball recruits in Pennsylvania, one of whom transferred from Virginia and wouldn’t have been eligible under the new transfer rules.

John Niemi, the Kennedy Catholic athletic director, makes the point that all of those transfers were approved by District 10 hearings, but he understands why his school is drawing so much attention.

“I realize, we’re like the New York Yankees, OK?” Niemi said. “I get it, I get it.”

Kennedy Catholic isn’t only dominating the 1A division, where last season it beat teams by an average of 45.4 points. It routed four 2A teams by an average of 39 points, one 5A team by 29 points and a 6A team by 18.

Its only losses were to a 5A team and three teams that aren’t in the PIAA, so moving it up may not make much of a difference. But they’ll find out this year because Kennedy made the decision to move up, not one, but five classifications to 6A.

Bariski points to St. Thomas Aquinas, another 1A school in the WPIAL, as a different kind of example — of possible unintended consequences of the rule changes.

Aquinas is a tiny Catholic school with about 26 students per class, according to enrollment figures.

If it happened to find a short run of success that coincided with some transfers, this new formula would send it up to the next classification. Once there, there’s no way to move back down.

“Now what happens?” Bariski said. “Are they going to play 2A? They won’t win a game. So I don’t think that point system is going to stay around very long.”

“I realize, we’re like the New York Yankees, OK?” “I get it, I get it.” John Niemi, the Kennedy Catholic athletic director

Everybody has a plan

A week after the new competition and transfer rules passed on July 18, a group of representatives from over 150 schools met to call for the PIAA playoffs to be restructured.

While the transfer rule was looked at approvingly and the competition formula not so approvingly, the bottom line for the group was that playoffs need to be separated.

This grassroots group calls itself the Playoff Equity Summit.

Its most popular proposal is to revert to four classifications for the traditional public schools and create two classifications for the private schools. Within the current system, that would make 1A-4A traditional public school competition and 5A-6A private, Catholic and charter competition.

But other ideas abound. Some mention creating a 7A superclass, while others have suggested giving private schools multipliers when counting enrollment.

Williams doesn’t think it has to be that complicated, though. “I honestly believe that if we did institute it, separate divisions, in a few years, nobody would care and everybody would be happy,” he said.

The ramifications

There’s another side in this argument, another set of kids who would be affected if the playoffs split. That’s the private school students, who would face more time in travel to find competition, among other issues, if they no longer played in public leagues.

“It bothers me that it’s about winning championships,” Bariski said. “We’re all in this, as coaches and teachers, for opportunities and what’s best for kids. … That kind of irks me a little bit.”

And, as Niemi and Bill Cleary, the Serra Catholic athletic director and girls basketball coach, pointed out, no one complains when their private school teams are losing.

And the basis of traditional public schools’ arguments are off, as well, Bariski and Cleary said. Public schools complain that private schools can take students from anywhere, but public schools can technically take tuition students, too.

There’s a lot that gets overlooked, they add, like the fact that Bariski’s team plays up two divisions by choice. Or that Cleary’s students voluntarily play on muddy fields instead of the nice turf that many public schools have.

Patient but not passive

In the PIAA’s eyes, all of this is just talk.

As far as it’s concerned, nothing can be done unless Act 219 is amended. And that means nothing happens until and unless Pennsylvania lawmakers do something.

“The interpretation that law is giving to us is that championships should not be separated,” said Barber, a member of the PIAA board. “So, pending the review and any change in that process, that will drive what I believe the organization will do.”

Meanwhile, the Playoff Equity Summit has held out the possibility of splitting from the PIAA. “We call that the nuclear option,” said Rich, who is one of the superintendents leading the movement.

It’s not the preferred choice, Rich said — he would much rather reform the system from within than leave — but it’s on the table.

Many predict a long fight, but Bariski feels that separation is inevitable.

“I don’t think it’s going to go away until the traditional schools get their way,” Bariski said. “And I don’t think that will make them happy, either.”

All about the kids

The driving force behind the debate is the kids. Or at least, that’s what the public school representatives say. Some of the private schools have their doubts.

“I’d say 90 percent of the kids don’t even know,” Bariski said. “And I’d say even 90 percent of the kids don’t even know all this transfer stuff is going on unless they’re going to transfer.”

Cathedral Prep from Erie has won four state championships, but it plays mostly private schools on its way to the title, including during the regular season. Separation wouldn’t make much of a difference.

It’s not much of a conversation among the students nor the parents, said Kaden Swanson, a manager of the football team, and his father Jeffrey Swanson, the president of the Boosters Club.

“It’s a big shrug of the shoulders,” Jeffrey Swanson said.

Cathedral Prep students cheer on the football team during the 4A semifinal playoff game against Bishop McDevitt. The students made a three-hour trip to see their school win 48-7. ~ photo by Giana Han

There’s no doubt the public administrators know more about the topic because they’re the ones with the authority to drive the protest movement, but the public school student-athletes are aware of the differences between themselves and their private counterparts.

When Cal Fisher’s soccer team at Riverview High School outside Pittsburgh won his senior year, it beat teams by an average of almost five goals a game, and most of its losses were close.

But, when Riverview played North Catholic, it lost 7-0 and 7-1.

“They would just blow us out,” Fisher said. “And they would do that to every single team in our division.”

While Fisher didn’t mind the competition, he said there were conversations among the team about the fairness of the situation with North Catholic as well as how his team’s best players all happened to end up playing for Central Catholic, another team in the WPIAL.

Nonetheless, his sense is the players were less wound up about the situation than their moms and dads.

“I feel like sometimes the adults take it more seriously than the kids do because we’re just really there to play and have fun with it,” Fisher said. “And I think sometimes they get up in the game and take it more seriously.”

~ 12/12/2018