.

.

From his vantage point in nearby Baltimore, activist and author D. Watkins has heard the cries of dismay from Washington, DC, as “the gentrification wave has washed in and drowned the black population over the past 10 years, unfairly displacing many of those residents.”

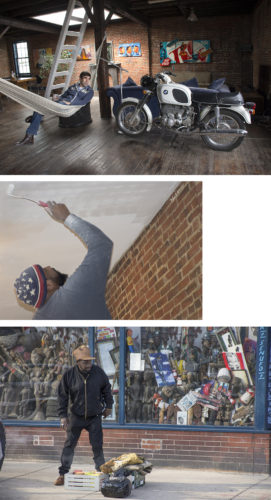

Baltimore gentrification in a nutshell: The three Roberts at 1100 Hollins. On the first floor is artist Robert Williams. On the second floor is construction worker Robert Lee Jr. On the third floor is building owner Robert Meyer. Photos by Mriganka Chawla

If DC gentrification is a tsunami immersing black neighborhoods in a sea of white hipsters, the rate of change in Baltimore is more like a slow riptide on Chesapeake Bay, dangling the promise of economic revival on the surface while tugging away at the human foundation of the city’s neighborhoods.

During the spring of 2017 students from Penn State and Morgan State universities learned of the cultural impact of urban redevelopment on black neighborhoods by studying the writings of intellectuals like Watkins and Ta-Nehisi Coates. They studied data and maps. Then they traveled into the neighborhoods, walked down streets, knocked on doors and met people whose lives are being impacted by the riptide of change.

Writer/photographer Mriganka Chawla found three men named Robert in a house next to the historic Hollins Market. Even though the three men are in the same building, each is experiencing the neighborhood’s gentrification in a different way.

The Robert on the first floor is a jazz musician and artist who sells clothes and objects from Africa. He is seeing his neighbors get wealthier and whiter. The Robert on the second flood is paying his rent by helping to renovate his landlord’s building. The third Robert wanted a New York loft apartment, but couldn’t afford one. Now he owns several buildings in the Baltimore neighborhood and has the loft of his dreams in the third floor at 1100 Hollins.

Bernadette Buckson is rebuilding her life by helping to tear down her old neighborhood, by hand. Photo by Jingling Zhang

A company called Brick + Board buys salvaged building materials from crews that are dismantling some of Baltimore’s 17,000 vacant buildings by hand. Video journalist Jingling Zhang started at the beginning of the salvage process, following it to its origins and discovering Bernadette Buckson, a recovering addict who is putting her life back together by literally tearing down the neighborhood where she lives. Video reporter Shuyao Chen tracked the salvaged lumber and found that the old growth wood being salvaged from row houses is being transformed into unique furniture and decor by artists like Joshua David Crown.

Sometimes the factors that halt neighborhood decline and make it attractive to renovators can be a little unexpected.

The Reservoir Hill neighborhood lost its business district to urban renewal decades ago. The neighborhood used to be largely Jewish and once ornate row houses still have the interior woodwork that speaks to the a time of wealth. Today Reservoir Hill is 93 percent black and most families have incomes hovering near the poverty line. But the quality of life has rebounded from its low in the turbulent 1960s. The change has been driven, in part, by the transformation of the business district from vacant lots to, of all things, a farm. Video reporter Min Xian found that the agricultural oasis is providing an infusion of fresh food, fresh vistas and even a few jobs.

Index to stories

-

- Rebuilding Baltimore: A Tale of Three Roberts

Text and images by Mriganka Chawla - Salvaged Wood Reborn

Text and video by Shuyao Chen - Deconstructing row houses to rebuild a life

Text and video by Jingling Zhang - From Eyesore to Oasis

Text and video by Min Xian - Synagogue Remains a Constant in Evolving Reservoir Hill

Text and video by Sara K. Isenberg - The St. Francis Power Project: Improving Lives in Reservoir Hill

Text and photos by Georgiana DeCarmine - Jack’s Poultry has fresh chicken, loyal customers, but no employees named Jack

Text and photos by Yukai Peng - Two Barbers, One Mission

Text and photos by Jorden Green

About this project

(These stories were reported for the Baltimore Project, a multimedia workshop exploring the impact of urban development in Baltimore. It is a collaboration between The Donald P. Bellisario College of Communications at Penn State University and The School of Global Journalism and Communication at Morgan State University.)

.

- Rebuilding Baltimore: A Tale of Three Roberts