Changes in technology have made the courtroom artist an endangered species in U.S. courts.

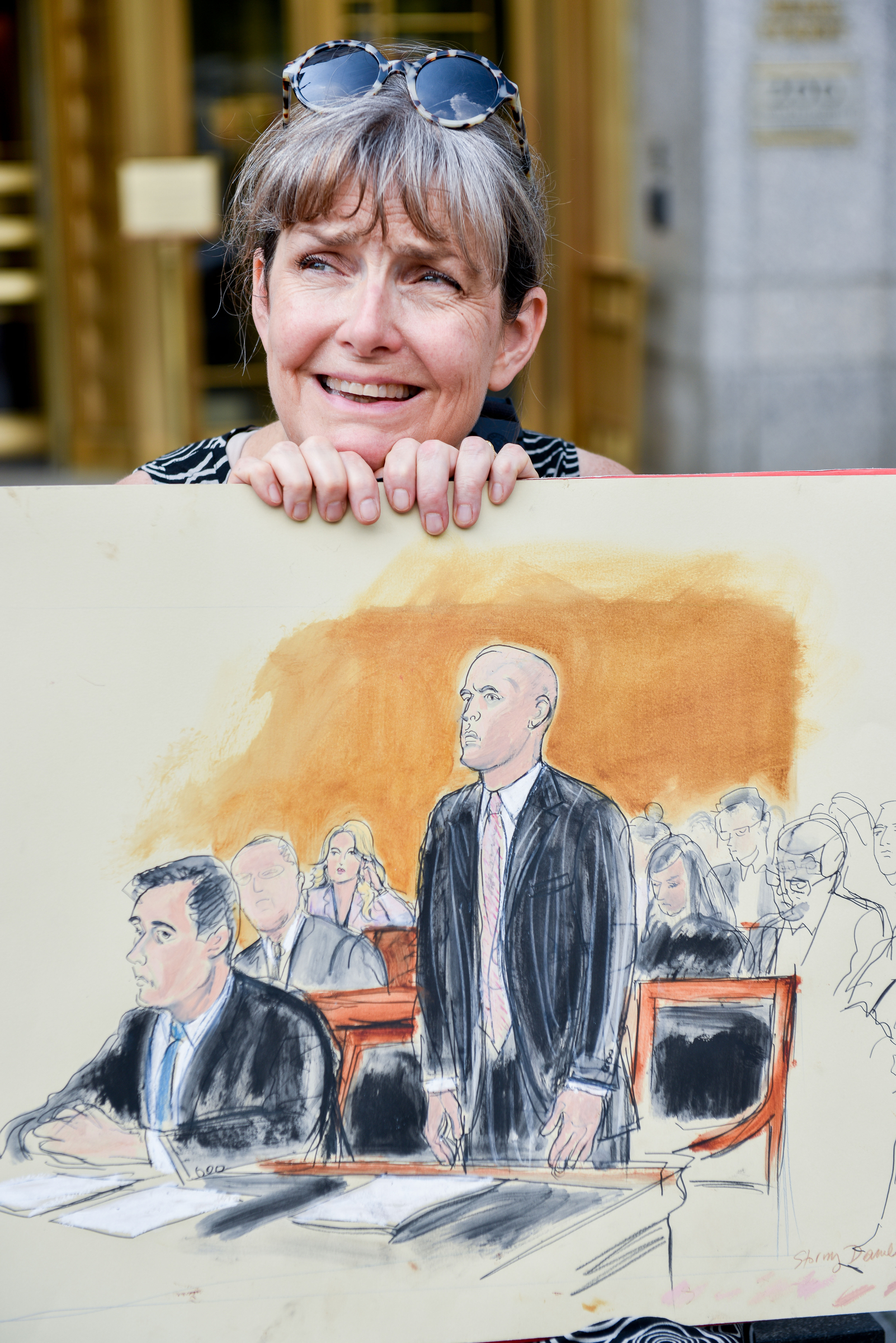

Courtroom Artist Elizabeth Williams' sketch of Harvey Weinstein. ~photo by David Handschuh

At an arraignment in room AR-1 of the New York City Criminal Court building in May, Hollywood film mogul Harvey Weinstein was charged with rape and a criminal sex act.

Six years ago, in a small courthouse in rural Bellefonte, Pennsylvania, former Penn State football coach Jerry Sandusky was convicted of multiple sex crimes against underage boys.

Timothy McVeigh, in 1997, was sentenced to death by lethal injection in a Denver courthouse for the murder of 168 people who died in a bombing at the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City two years prior.

Art Lien and Elizabeth Williams have gone face-to-face with all of these individuals in all of these courtrooms – not with briefcases, logic or Harvard Law degrees, but with pencils, oil pastels and metal tins of watercolor paints.

Lien and Williams are among a dwindling number of courtroom artists left in the United States who capture what are typically unseen moments of the judicial system — giving the public glimpses of scenes and people that are, at times, off-limits.

In an age of technology, social media and the internet, the job of courtroom artist seems to be an anachronism — described as “archaic” by Lien.

“We’re a throwback that’s still alive. We’re like the cockroach that survived the Ice Age,” said Williams, who has been practicing her craft for more than 25 years.

In New York alone, where she is based, Williams said there were roughly 17 artists actively doing work for news organizations during the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Now, Williams said, across the United States, there are only about 14 to 16 artists “occasionally” doing courtroom art. As for those who work exclusively as court artists, she estimated, there are only four or five left in the U.S.

Lien estimates there are fewer than 10 fulltime courtroom artists in the country.

Whatever the number, Lien and Williams said they are both still working.

“I thank my lucky stars daily,” said Williams.

***

The first time Lien undertook the job of courtroom artist — covering the 1977 trial of former Maryland Gov. Marvin Mandel who was convicted of political corruption — he got fired.

“I had this non-absorbent paper and I was trying watercolor on that. And every time I tilted it, everything ran — I just did a terrible job,” Lien said. “I told them ‘Let me just go back tomorrow, you don’t even have to pay me.’”

Knowing the paper he used was what botched his drawing, Lien returned the following day with a different material. He got his job back.

Unlike many courtroom artists who now work exclusively as freelancers, Lien has worked under contract with NBC since 1980. He graduated from the Maryland Institute College of Art with a degree in painting and printmaking.

As an American growing up in Switzerland without knowing French or the other native languages, Lien said his teachers encouraged him to write a word in English and then draw an accompanying picture. He settled on going to art school after graduation.

“I was aimless, and [art] was the one thing I did well,” he said.

Lien has sketched in courtrooms all around the country. The D.C. based artist has even drawn proceedings at the U.S. Supreme Court. ~ photo by Hannah Byrne

Lien began looking for work and eventually met Howard Brodie, a World War II combat artist who worked for CBS. Brodie took him under his wing and into the U.S. Supreme Court for the first time.

Forty-one years later, with a standard mechanical pencil, water colors and brushes of varying sizes, Lien not only covers trials around the country, but he also sketches proceedings of the United States Supreme Court.

To succeed in courtroom drawing, Lien, who is based in Washington, said he must anticipate what will occur. To prepare, he also reads up on arguments and cases.

“If you put your head down looking at your drawing, then you’re going to miss what’s going on. It’s taken me a long time to learn that,” he said. “And, sometimes you need to not draw and just see what’s happening, and then draw from memory.”

To Williams, the job of a courtroom artist is only getting faster and faster as the Internet has changed the dynamic and deadlines of the daily news cycle.

She began her career after graduating from the Parsons School of Design in New York. She then moved to Los Angeles to pursue a different kind of art.

“I wanted to be a fashion illustrator, and I couldn’t do it,” Williams said. “There wasn’t any money in it — it was terrible.”

On a whim, a college professor recommended she try courtroom sketch drawing. Williams, frustrated and discouraged, wanted nothing to do with the trade.

“You wanted to be a book illustrator or a general illustrator or a magazine illustrator,” she said. “All of these fabulous things were going on — nobody wanted to do courtroom art. It was sort of this lowbrow thing.”

Courtroom Artist Elizabeth Williams carries her sketch of Attorney Michael Cohen as she leaves Federal Court in Foley Square. ~photo by David Handschuh

But on days off from what Williams called her “five crappy jobs,” she began to draw the courts. Like Lien, Williams found comfort in a mentor, Bill Robles, an artist who has drawn the likes of Charles Manson, Michael Jackson and O.J. Simpson.

She met Robles while covering a Hillside Strangler hearing in Los Angeles in the early 1980s. Robles told her that she wasn’t “half bad” and put her in touch with a local television assignment editor. From there, her career as a court artist took off.

“I got lucky,” she said.

She finds courtroom drawing difficult because her subjects — lawyers, judges, plaintiffs and defendants — are constantly moving.

“It’s not like in a drawing class where you have a model on a podium,” Williams said. “To this day it’s a challenge.”

Working with oil pastels, paint and a pad of 20-by-27-inch Fabriano paper, Williams goes into each drawing knowing the outcome might not always be what she expects.

During a recent interview in New York, she said, “It’s the likeness, it’s the thing you’re constantly concerned and worried about.”

Pulling a large drawing out of her Army green-colored portfolio, Williams held a finished piece of Michael Cohen, President Trump’s former lawyer, swearing the oath in court.

~photo by David Handschuh

She captured his silver hair, cloudy, under-eye circles and bushy eyebrows slanted in a downward frown. Courtroom walls of dark sienna glared against his pale complexion.

It took Williams 17 attempts to nail down the likeness of Cohen, she said.

“We were all struggling, I’ll tell you that — it was a struggle. And it happens a lot in my job,” she said.

***

On May 25, Harvey Weinstein burst through a single oak door — from a holding pen with iron bars — to a dimly lit courtroom full of reporters, lawyers and police officials.

“It reminded me of hunters bringing in their game prey,” Williams said. “It was the craziest thing.”

A seasoned courtroom artist, Williams has drawn everyone from Bernie Madoff to Stormy Daniels to John DeLorean to the Times Square Bomber and Weinstein.

She recalled that Daniels looked bored in court.

“There’s no cameras, so I’ve got to be the camera,” Williams said. “It’s a big job.”

“It’s the likeness, it’s the thing you’re constantly concerned and worried about.” She said it took 17 attempts to get the likeness of Michael Cohen correct. ~photo by David Handschuh

Lien, working out of Washington, has a similar “who’s who” of big cases.

The Underwear Bomber, Umar Farouk AbdulMutallab, who made his courtroom debut in Detroit in 2010, appeared before a judge for less than five minutes. Lien, recalling it as a “crazy day,” was able to produce two drawings out of that brief time.

And, while covering the Sandusky trial, Lien said his strategy was to observe Sandusky’s reactions and emotions to convey into his drawings.

“It was very odd,” Lien said. “He just seemed to smile most of the time.”

People have taken notice of the artwork of Lien and Williams. While Lien has received letters from housewives in Kansas, Williams’ drawings are displayed in the Library of Congress.

But sometimes, the people who reach out are not always so friendly.

While covering a trial in 1979, in which five members of the Communist Workers Party were murdered by Nazi and Ku Klux Klan members, Lien was approached by a defendant in the courtroom.

“One of them came up to me, and it was very scary. There was this evidence table with all these bats and guns and other weapons, and he said, ‘Boy you better not be sketching my wife, I’ll kill you,’” Lien said.

The McVeigh trial, one of the cases Lien is most proud of, spanned a few months.

McVeigh was executed in 2001. His co-conspirator, Terry Nichols, received a life sentence and currently resides at the Federal Correctional Institute in Florence, Colorado.

“We did a Nightly News story every single night in that Oklahoma City bombing trial. That was the hardest thing I ever did,” Lien said. “There was one morning when they had 30-some witnesses one right after the other — and this was before lunch — and I managed to sketch every single one of them, roughly.”

***

In his Colorado office, Reid Neureiter has four courtroom drawings neatly framed against a khaki-brown background, including a depiction of Neureiter’s time as part of the defense counsel for Nichols.

“After the artist licenses the use of the image to the media, it kind of disappears in terms of its utility — except for lawyers,” Neureiter said.

Now a United States magistrate judge, Neureiter works in Colorado where cameras are allowed in courtrooms. Judges can deny this access depending on different circumstances.

Neureiter said he’s not sure how helpful a photographer or a courtroom artist can be in communicating information.

“It’s really hard to communicate the ‘touchdown catch’ in a court trial,” Neureiter said. “I think that courtroom sketch artists are useful to communicate to the public what people actually look like, but I don’t think it’s a method of informing people about what’s going on in the case.”

Tom Kline, a prominent Philadelphia lawyer, said he has mixed feelings regarding cameras in the courtroom.

He said the courtroom operates in a more “insular and isolated” environment without cameras intruding in that space. And, without cameras able to record the newsworthy or noteworthy events, courtroom artists become a “valuable secondary tool.”

“I look over their shoulder and think ‘Hmm… that’s interesting,’ what they see and how they’re interpreting it,” Kline said. “But it’s an interpretive report, much like a reporter reporting on what they’ve seen — I view it as an extension of reporting.”

Keith Eldridge, a general assignment reporter working for KOMO-TV in Seattle, said his station only uses courtroom artists every once in a while for big federal cases such as drug and human trafficking.

Other local television stations around the country, sometimes teaming up with local newspapers, reserve hiring courtroom artists for only celebrity-type cases.

Dennis Reinaker, president judge of the Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, Court of Common Pleas, said he hasn’t seen an artist in his courthouse for about 15 years. Early on his career, Reinaker said one local artist would come in to draw some more of the high-profile cases.

To him, the purpose of the artists was to serve as a “visual depiction” for the readers of local newspapers — to leave them with a more personal connection to the events.

Describing himself as “old school,” Reinaker said he prefers artists to photographers in court. Reinaker has banned cell phones in the courthouse, because he wants to prevent people from using their phones to take photos or record proceedings.

The Pennsylvania legislature has a bill before it that would increase penalties for anyone caught using a cell phone in courtrooms.

In 1981, the United States Supreme Court allowed each of the 50 states to adopt rules permitting cameras and other recording equipment into courtrooms, according to the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press.

State laws and court practices governing television cameras and still photographers vary widely, with some permitting full access and others limiting coverage to certain appellate proceedings.

Last year, U.S. Sen. Chuck Grassley (R., Iowa) and Amy Klobuchar (D., Minnesota) introduced a bill titled “Sunshine in the Courtroom Act” that would give federal judges discretion, with some restrictions, to allow cameras in courtrooms. That legislation remains in the Judiciary Committee.

Neureiter predicted the rule won’t change anytime soon. He said when cameras televise proceedings, courts can be transformed into circuses. He cited the recent confirmation hearing of then-Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh.

“The televised Kavanaugh hearings are an example where people get up and protest and get dragged out screaming,” Neureiter said. “Are they doing that for TV or are they doing it to send a message to the senators — who knows? But that’s not something you want to have happen in a federal courtroom.”

Williams shows how her sketch of Michael Cohen evolved. ~photo by David Handschuh

***

Lien said the courtroom artist community is growing smaller, and he attributes to what he said is the “inevitability” of more judges allowing cameras in courtrooms to the changing dynamics of reporting the news – fast-paced information in constant demand.

“There’s also something like the perp walk. You didn’t see it like you do now,” Lien said. “I think the government in many cases is willing to give mugshots and perp walks and things like that — and then the graphics department can do something really snazzy with it.”

Stan Wischnowski, executive editor of the Philadelphia Media Network, which includes The Philadelphia Inquirer, said the last time his newspaper used a courtroom artist was in 2014 for a Sandusky hearing. Before that, it was in 2012 during proceedings of a Philadelphia priest abuse scandal.

Though Wischnowski said value in courtroom artists still exists, “the era may be dying on that industry.”

Williams remembered vividly the treatment of courtroom artists to be very different from what it is now – having drivers, staying in top hotels and getting flown around to different trials were just a few of the perks.

Judge Reinaker said he also looks at courtroom artists with a touch of nostalgia.

“It’s just kind of sad. It seems like another aspect that’s dying out of what traditionally has been part of some of these very high-profile cases,” he said. “It just kind of seems like that’s something that I remember from the past that probably is just not going to be part of the situation anymore.”

10/24/2018